OPM Data Breach

The OPM Data Breach

Abstract

On June 4th, 2015, the Washington Post published a reveal that the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM) had been hacked and majorly compromised (Nakashima 06/04/15). As the overseeing body of the USA’s federal employees, the their sensitive personal information exposed. Furthermore, the article suggests that China was likely to blame. The following reactions from the media were that of shock and accusation. The heavy media pressure was so prevalent and ubiquitous that it likely had a host a negative effects on the as of yet investigations of the OPM breach. Beyond political sensitivity, all the technical aspects of the hack are as of yet unknown, but in the following you will find the vulnerabilities that lead to the hack and most concretely or likely techniques that were utilized.

OPM Server Framework Overview

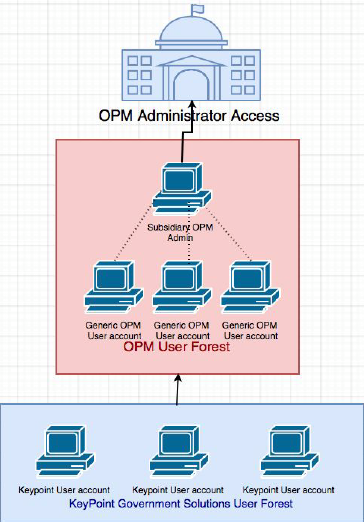

The Office of Personnel Management stores their data on a Microsoft Windows Server Platform, which is unique because it uses the Active Directory (AD) architecture. The AD contains a user forest system, which is almost a forest-like organization of users. Users with highest credentials (i.e., administrators), are at the top of the user forest. At the bottom are the lowest login credentials, such as independent contractors or entry-level workers. If users are part of a user forest, they can see all other users in the AD and their corresponding privileges. However, a user cannot access the data unless he has the proper credentials.. KeyPoint is a government contractor that is in charge of conducting security clearances on behalf of OPM. After an internal data breach in which login credentials of several KeyPoint employees were stolen, the attackers were able to gain initial non-admin access the OPM network.

Figure 1.1: OPM’s Active Directory architecture with a user forest

Exploiting Microsoft’s Vulnerabilities

Active Directory Privilege Escalation is a method from which an attacker compromises a non-admin account and is able to gain privileges through attack vectors until eventually becoming root.

Exploiting the LSASS Vulnerability Via Mimikatz

The Local Security Subsystem Authority Service (LSASS) is in charge of saving a user’s login credentials to memory in order to provide single sign-on capabilities on the Windows operating system. This program is executed after a user logs into a server or personal computer. On a Windows 2008 Server or earlier, the LSASS writes all of the user login credentials that have logged into the network in the same memory address. Mimikatz is a software that exploits this vulnerability and returns a memory dump of all user’s credentials that have logged into the system on the same session. Therefore, after possessing an initial access to the OPM network, the attackers were able to steal many OPM employees login information, some of which belonging to admin users. However, on many systems that run Windows, passwords are not stored in plaintext inside the Domain Controller – their NTLM Hash are stored instead. This prevented the attackers from directly obtaining plaintext usernames and passwords; instead they would have to exploit another Windows server vulnerability to compromise the account.

Exploiting the NTLM Authentication Protocol Vulnerability

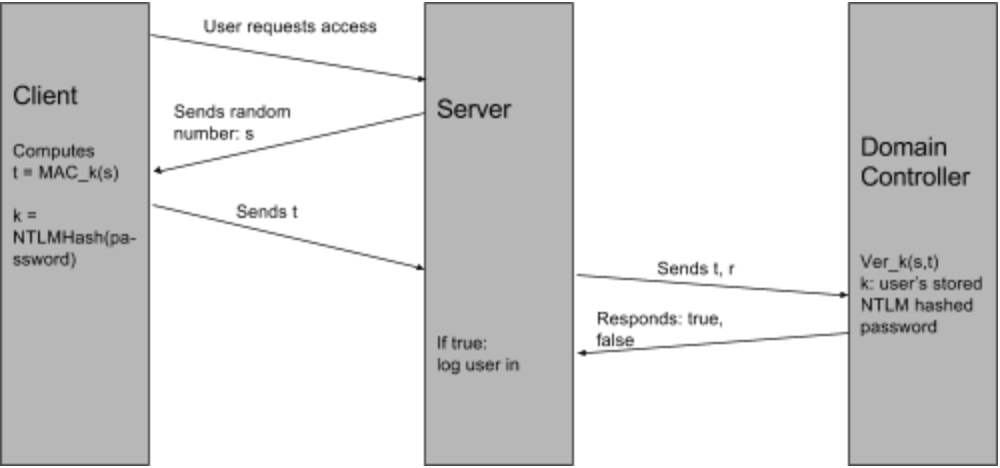

Figure 2.1: Diagram representing the different procedures of the NTLM authentication protocol.

Based on the above diagram, the NTLM Authentication protocol never verifies the user’s plaintext password. Therefore, if an attacker were to get a user’s password as an NTLM hash, along with its username in plaintext, he could authenticate as his victim. This is called a ** Pass-the-Hash attack **, and it was used by the attackers in order to compromise admin accounts inside the OPM network after stealing their hashed passwords.

Installing the Remote Access Trojan

After gaining root access into OPM’s network, the attackers instaled a Remote Access Trojan into the machine, which is a malware that communicates over HTTP to an external network that belongs to the attacker. Innocuously named after McAfee’s software mcutil.dll to fool sysadmins, the attackers were able to read and steal the SF-86 forms that were stored inside OPM’s network.

Aftermath of the attack

As a result of this attack, 19.7 million government security applicants and 1.8 million of their co-habitants, a total of 21.5 million, had their data compromised. Data that was stolen included addresses, dates of birth, pay histories, pension information, ages, gender, race, and fingerprints. In response the former head of OPM, Katherine Archuleta, was forced to resign. An additional government response to the attack was to instigate a 30 day security sprint to improve and standardize security measures across all government organizations.

There are few ways to prevent such an attack from happening. One way is to use 2-factor authentication. If a person logs into an account, then the server would send a notification to another device or source from which the owner of the account can verify the login. If the owner verifies the login, then the server responds by logging in the user. Using a 2-factor authentication system would have prevented pass-the-hash attacks or unauthorized logins, because the owner of the account would have to approve the login in order for the user to access the account. Another way that OPM could have prevented the data breach was to change compromised credentials from KeyPoint. Access to KeyPoint allowed the hackers to access OPM’s Active Directory; preventing hackers from using stolen credentials would have prevented the entire attack. The compromised credentials should have been altered or removed to prevent this breach.

The Various Non-Technical Influences

Beyond just being technical complexity, the OPM hack is further complicated because of political influence and the media. First and foremost, the OPM hack is inherently political. While most hacks have the straightforward aspect of being for financial gain, this one is muddled by inscrutable political influence. Though there’s still no consensus, multiple independent security firms believe that the attack was performed by a possibly state funded Chinese group. The two major pillars of belief are that China possesses both the capability for the attack and the ability to leverage to unique stolen data. After all, independent cyber criminals would have more use for liquid assets, a government would be more likely to compile dossiers on federal employees. Any political statement the U.S. publicly releases will be heavily influenced by pragmatic politics; instead of being objective information for the public; influenced national power dynamic in other political arenas. Beyond America, any attempt to apprehend the people responsible will ultimately have to be Chinese. Given that the Chinese Government has claimed to have caught the hackers but completely refuses to release any of their identities, details or techniques of the group, one might question the legitimacy of those statements (Nakashima 12/02/15). Beyond political effects, the media blitz that followed the original expose raises troubling issues. It is my personal belief that the media’s deep need for attribution lead to a somewhat substandard job on the part of independent security companies. Given that the first major theory for attribution is a group called Deep Panda is responsible (Krebs) and the second is that it wasn’t Deep Panda (Hesseldahl), it would certainly suggest a lack of proper coordination and peer review before attribution. I attribute this phenomenon to the media cycle, making any speculation so lucrative in terms of attracting publicity, that firms cannot resist making large claims without ample critical inspection.

Conclusions

There are many implications and take aways from the vast array of events that spiralled out of the OPM hack. First and foremost is the need for the US government to use up to date and secure architectures and machines in all aspects of governing; a wider adoption of two factor security would also be indispensible. Beyond that, there seems like there’s a definite need to create have a greater independent source for security analysis. One that can gain access to otherwise classified government material while simultaneously staying unbeholden to political, media and market influence. Perhaps the UN could could form some manner of independent cyber security analyzer team, as international cooperation in this regards isn’t spectacular. Or independent security companies could come up with some sort of internal sharing agreement prior to publishing findings, to prevent the public consumption of wildly dissenting views that they have no ability to technically process and have to take on faith. Regardless, the OPM hack and it’s aftermath goes to show that there is much ground to cover in cyber security, not only on the technical level, but on the level of legislature and public management.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ann-Ming Samborski and Professor Sharon Goldberg for their feedback. This work was done without any outside collaboration.

Work Citation

- Dell SecureWorks Counter Threat Unit Threat Intelligence. “Sakula Malware Family Threat Analysis.” SecureWorks. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “FACT SHEET: Enhancing and Strengthening the Federal Government’s Cybersecurity.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “FBI Alert Suggests OPM/Anthem Malware Link.” HIPAA Journal. N.p., 04 July 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Francou, Yoann. “Malware Sakula - Evolutions v1.x (Part 1).” Airbus D&S CyberSecurity blog. N.p., 09 Nov. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Gentilkiwi. “Gentilkiwi/mimikatz.” GitHub. N.p., 09 Apr. 2017. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “Impact of OPM breach could last more than 40 years.” Fedscoop. N.p., 26 Dec. 2016. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Hesseldahl, Arik. “FireEye Identifies Chinese Group Behind Federal Hack.” Recode. Recode, 19 June 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Krebs, Brian. “Krebs on Security.” Brian Krebs. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “Microsoft NTLM.” Microsoft NTLM (Windows). N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Nakashima, Ellen. “Chinese Breach Data of 4 Million Federal Workers.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 04 June 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Nakashima, Ellen. “Chinese Government Has Arrested Hackers It Says Breached OPM Database.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 02 Dec. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “OPM Chastised for Lack of Security Analytics:.” DLT Blog. N.p., 28 Dec. 2016. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Peralta, Eyder. “China Says U.S. Allegations That It Was Behind Cyberattack Are ‘Irresponsible’” NPR. NPR, 05 June 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “Press Briefing by Press Secretary Josh Earnest, 6/5/2015.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Sean Gallagher - Jun 8, 2015 3:00 pm UTC. “Why the ‘biggest government hack ever got past the feds.’ Ars Technica. N.p., 08 June 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- Stuart Leavenworth - McClatchy Foreign Staff. “China denies role in recent U.S. government security hack.” McClatchy DC | McClatchyDC.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

- “Technical forensics of OPM hack reveal PLA links to cyber attacks targeting Americans.” Flash//CRITIC Cyber Threat News. N.p., 07 June 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.