The SSL DROWN Attack

The SSL DROWN Attack

Abstract

The DROWN attack, publicized in March of 2016 by a large team of researchers around the globe, is a cross-protocol attack from TLS to SSLv2 that allows an attacker to decrypt the pre-master secret of a TLS handshake, thereby gaining access to all communication between the client and the server. While this attack has not been used–at least not that anybody knows of–it still poses a serious and legitimate threat to any server with both TLS 1.2 and SSLv2. As of right now, only Mozilla Firefox has started allowing TLS 1.3, which should protect against DROWN if implemented properly.

Discovering DROWN

The DROWN attack, a cross-protocol attack on TLS using SSLv2 vulnerability, was first reported to OpenSSL on December 29th 2015. Full details of DROWN were later publicly announced on March 1st, 2016. DROWN, which stands for “Decrypting RSA with Obsolete and Weakened eNcryption,” was developed by researchers at Universities around the world, along with the OpenSSL Project, Two Sigma, and Google. In addition to the announcement, a patch that disables SSLv2 in OpenSSL was also released in March 2016. However, the patch alone was not sufficient to mitigate the attack completely; the only way to do this was by disabling SSLv2 on all servers. The DROWN attack affects any service–including HTTPS–that relies on SSL and TLS. Although SSLv2 is known to be an obsolete and insecure protocol, there are still servers that support it, even if their services are actually encrypted with TLS. DROWN takes advantage of HTTPS servers that still allow SSLv2 connections, which comprised 16% of all HTTPS servers when DROWN was released. Because of key reuse, which is when the private key is used on an entirely different server that allows SSLv2 connections, an additional 17% of HTTPS servers were also vulnerable to the attack, for a total of 33% of servers in March of 2016. And yet, as of April 2017, no DROWN attacks have been reported.

The Buzz About Drown

Many popular websites such as BuzzFeed, Yahoo, and Alibaba were among the 11 million websites, mail servers, and other TLS-dependent services at vulnerable to the attack. Yet, there were very few press releases and acknowledgements by these sites of their potential vulnerability to the DROWN attack. Salesforce took a proactive approach and published the following:

“Trust is our #1 value and we take the protection of our customers’ data very seriously… We have evaluated the vulnerability and potential impact to Salesforce customers. At this time, we do not believe Salesforce servers are vulnerable to this attack.”

If DROWN were to be exploited in the wild–or, more specifically, if information was released regarding such an attack–there would be many more statements released from companies. That said, a lot of the technical press have covered what DROWN is and its risks in the form of blogs and articles. For example, Ars Technica’s risk assessment that was published the day the attack was announced. While the DROWN attack has found its home in the technical press, it is not as relevant in the popular press, likely because no attack using DROWN has yet been discovered.

The Attack

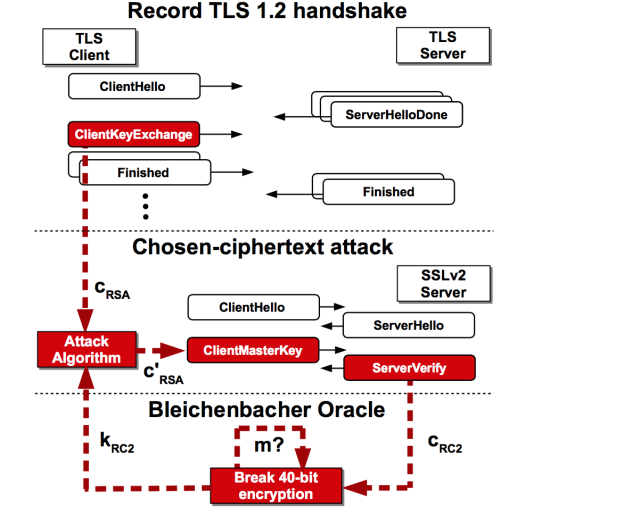

The DROWN attack works because of three main weaknesses: SSLv2 is weak to a Bleichenbacher attack, uses 40-bit export ciphers, and shares a certificate–and private key–with TLS. This allows an attacker to decrypt an RSA key exchange message sent over a secure TLS connection by taking that ciphertext and breaking it in SSLv2.

The key exchange is one of the final messages sent in TLS’ handshake. The handshake begins with a ClientHello, and the server responds with its ServerHello, including its certificate with the public key. Using the public key, the client encrypts a pre-master secret (which will be used to create the session key) concatenated with the public key (which serves to ensure the authenticity of the encryption). The client says they’re done, and the server says that it has everything it needs, and now the client and the server can send all sorts of information with the comfort of encryption. This handshake, for the purposes of DROWN, is not the real issue. SSLv2’s handshake, on the other hand, is vulnerable. It starts with a ClientHello, followed by a ServerHello, and then the client sends the MasterKey, which the server then verifies. This makes it trivial to verify whether or not your attack has been successful, and allows the attacker to verify their attack’s efficacy.

| The Bleichenbacher step–the first step in DROWN–involves throwing a thousands of different multiples of the ciphertext and seeing what sticks. If the Bleichenbacher oracle responds saying it could be decrypted, then the attacker gains knowledge of the plaintext. The attacker repeats this process until they can decrypt the pre-master secret. This works because the standard SSLv2 and TLS uses for RSA keys, PKCS#1 1.5, begins with x00 | x02. It is much easier to find a ciphertext that has a message that starts with 02 than a message with fewer deterministic elements. So if the attacker has an oracle, they can send thousands of ciphertexts to the server, learning bits of the actual plaintext they’re trying to decrypt each time. |

Figure 1: A diagram of how the DROWN attack works

Unfortunately, SSLv2 can be the oracle this attack needs. If the ciphertext the attacker sends is decryptable, it responds with an obfuscated version of the pre-master secret. If it isn’t, it responds with an obfuscated version of a new pre-master secret. If the attacker sends the same Bleichenbacher ciphertext twice, and can determine if the two pre-master secrets sent back are different (meaning the ciphertext the attacker sent was not decryptable) or the same (the ciphertext was decryptable), then the attacker has an oracle. Because SSLv2 obfuscates these pre-master secrets using a key with only forty bits of secrecy, the attacker can determine whether the two are the same or different. Forty bits are easily brute-forceable. Once the attacker brute forces this key, they now have an oracle, and the Bleichenbacher attack is executable.

Because SSLv2 and TLS use the same RSA private key, by decrypting the pre-master secret in the SSLv2 implementation on the server, the attacker now has the pre-master secret for TLS on the same server. While this is a fairly costly procedure, as Bleichenbacher’s attack requires many calls to the server (it’s called the “million-message attack” for a reason, but with recent improvements to its implementation it would be more apt to call it the “thousand-message attack”), it is still a weakness. Any server implementing both SSLv2 and TLS 1.2 is vulnerable.

DROWN Prevention and Future Steps

The solution to preventing the DROWN attack is quite simple: disable SSLv2 on all web servers. Since DROWN is a server-side vulnerability, there is unfortunately nothing that the user can do to protect themselves from the attack. As long as the web server they are accessing allows SSLv2 connections, the user’s communications are vulnerable. It is important to note that even if one web server does not allow SSLv2, it is still vulnerable if it shares a private key with an SSLv2-enabled server.

Moving forward, however, the new TLS standard (TLS 1.3) is designed to prevent the DROWN attack. This new protocol was finalized in the past few months, and a much needed release since 2008 when TLS 1.2 was defined. Many attacks, such as DROWN, FREAK, and POODLE led up to TLS 1.3. In this version, all the components of past protocols were scrutinized for their necessity and security. TLS 1.3, unlike its predecessors, does not support static RSA key exchanges, which allow for Bleichenbacher-style attacks. However, TLS 1.3 does not guarantee protection against DROWN if the server uses an old certificate which was used in TLS 1.2. Therefore, server operators should not use old certificates in conjunction with TLS 1.3. Although TLS 1.3 is not directly vulnerable to DROWN, most browsers do not support TLS 1.3 as it was only finalized at the end of 2016.

Figure 2: Timeline of the DROWN attack in relation to SSL and TLS versions

Incentives for Using the DROWN Attack

Because Diffie Hellman key exchange is not being used, there is no forward secrecy if the key is compromised. An attacker who would exploit DROWN would be able to decrypt messages both in the past and future, allowing them to obtain many pieces of sensitive information such as login credentials, credit card numbers, emails, and instant messages. In many common cases, an attacker could also impersonate a secure website or change what a user sees on the site. As a result, not only are companies with vulnerable websites affected, but so are their clients whose personal information can be compromised.

An attacker would exploit DROWN over other attacks due to its practicality. After observing 1,000 TLS connections, this attack only requires 40,000 connections to a victim server and 20^4 export cipher encryptions to decrypt 1 of the observed TLS connections. As a result, it requires only 2^50 computations in order to decrypt an entire victim’s key. When researchers were testing this attack, they only spent $440 on an EC2 instance on AWS to launch DROWN and managed to decrypt a victim’s key in under 8 hours.

Even though DROWN is a brute-forceable attack, according to researchers, there is “no reason to believe that it has been exploited in the wild” prior to their disclosure of the attack’s details. However, now that this information is known, it is possible that attackers may start exploiting it. Therefore, the researchers recommend that servers should start taking countermeasures as soon as possible. There are some hypotheses as to why DROWN has not been exploited in the wild yet. Many websites and domains started making countermeasures to DROWN as soon as the announcement was made, and in less than a month of the disclosure, the amount of vulnerable sites decreased from 33% to 28%. Furthermore, if a company had been attacked from DROWN, they may have not publicly disclosed information about this. For example, Yahoo did not disclose that they were hacked until 3 years after the incident had occurred.

DROWN’s Relevance Today

During the introduction of the PC in the 1990s, export laws in the United States required companies to weaken their encryption algorithms for their products that are available overseas in order to make it easier for the NSA to decrypt the communication of people abroad. As a result, only the first 40-bits of the 128-bit ClientMasterKey remained secret. Even though these laws have relaxed from 20 years ago, this allowed attacks such as Freak, Poodle, Logjam, and DROWN (which exploited the export-grade symmetric cipher) possible. Because of this, even though TLS 1.3 is not vulnerable to DROWN, if policy makers try to restrict the design of cryptography again out of good faith to protect their country, the weakened cryptography can lead to future attacks being discovered.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ann Ming for assisting us in developing our presentation.

References

- http://blog.securitymetrics.com/2016/03/drown-attack-ssl-what-you-need-to-know.html

- http://blog.securityscorecard.com/2016/04/26/drown-vulnerability-risk-what-you-need-know/

- https://arstechnica.com/security/2016/03/more-than-13-million-https-websites-imperiled-by-new-decryption-attack/

- https://blog.cloudflare.com/encryption-week/

- https://blog.cloudflare.com/the-drown-attack/

- https://blog.cryptographyengineering.com/2016/03/01/attack-of-week-drown/

- https://blog.qualys.com/securitylabs/2016/03/01/drown-abuses-ssl-v2-to-attack-rsa-keys-and-tls

- https://docs.secureauth.com/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=40043100

- https://drownattack.com/

- https://drownattack.com/drown-attack-paper.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DROWN_attack

- https://help.salesforce.com/articleView?id=000232941&type=1

- https://securityinaction.wordpress.com/2016/03/01/the-drown-attack-what-you-need-to-know/

- https://storageservers.wordpress.com/2016/03/02/drown-attacks-one-in-three-https-servers/

- https://timtaubert.de/blog/2015/11/more-privacy-less-latency-improved-handshakes-in-tls-13/

- https://trushieldinc.com/drown-ssl/

- https://twitter.com/petrakramer/status/681605921429131264

- https://www.arraynetworks.com/press-release/press-release-drown-vulnerability.html

- https://www.emazzanti.net/emazzanti-technologies-issues-drown-attack-warning/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/drown-attack-more-than-11-million-websites-risk-learn-dominic-ryles

- https://www.nccgroup.trust/us/about-us/newsroom-and-events/blog/2016/march/drown-attack-ssl/

- https://www.openssl.org/blog/blog/2016/03/01/an-openssl-users-guide-to-drown/

- https://www.openssl.org/blog/blog/2016/03/01/an-openssl-users-guide-to-drown/

- https://www.secplicity.org/2016/03/04/drown-vulnerability-daily-security-byte-ep-225/

- https://www.technobuffalo.com/2016/03/02/drown-attack-open-ssl/

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/mar/02/secure-https-connections-data-passwords-drown-attack

- https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/03/01/drown_tls_protocol_flaw/

- https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/current-activity/2016/03/01/SSLv2-DROWN-Attack