Yahoo Data Breaches

Abstract

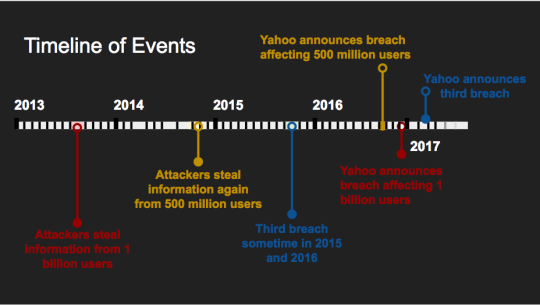

In August and December of 2016, Yahoo announced the discovery of two massive security breaches, affecting at least 1.5 billion users in total. Information stolen included their personal information such as email addresses, date of births, full names, encrypted and unencrypted security questions and answers, and most importantly: hashed passwords. Yahoo then announced in February 2017 that another security breach had been discovered, but did not give many details aside from believing it was done through forged cookies, where the attackers were able to forge cookies and be able to login to users’ accounts. The controversy surrounding these breaches not only comes from Yahoo’s existing security vulnerabilities, but also the delay in their response to these breaches, as most of the breaches occurred in 2013 and 2014 but were not announced until last year. As for the most recent announcement by Yahoo in February of this year, it’s believed that the attack happened sometime in 2015 or 2016, raising questions as to why there’s a large gap between when the breach happens and when Yahoo makes their announcement to the public.

Discovery

The figure below shows a brief timeline of events:

The late 2014 breach, announced in September 2016, was discovered sometime in July of the same year when a user on the dark web advertised a data dump containing information from over 200 million Yahoo users. The information included hashed passwords, emails, names, and matched up to accounts that already existed with Yahoo. This data dump had a price of 3 BTC, which at that time amounted to around $1800 USD. Yahoo made an announcement that they were “aware” of the sale post, but did not make their announcement of the data breach until late September.

As for the 2013 breach that affected over 1 billion users, it was discovered when a cybersecurity researcher, Andrew Komarov, discovered a similar sale post on the dark web. This one instead claimed to contain up to 1 billion accounts for the price of around $300,000. Komarov also noticed that one of the buyers inquired about if several U.S. government officials were included in the database, leading to speculations that the attacks were conducted by state sponsored groups. It also turned that over 150,000 accounts in the breach belonged to U.S. government employees.

Media Coverage

Yahoo was immediately slammed by not just the media, but by plenty of security researchers. This was not only due to their delay in response to the breaches as well as their announcements to the public, but also due to their gaps in security that allowed for the breaches to happen in the first place. Yahoo had an existing XSS vulnerability from late 2012 and early 2013 that allowed for attackers to steal users’ login cookies, which is possibly how the large data breaches happened in the first place. In addition to this, Yahoo’s use of the MD5 algorithm to hash their passwords, an algorithm that has been cracked already, spurred extra controversy.

Password Hashing

As part of the mid-2013 breach disclosed by Yahoo in December of 2016, they admit that, at “the time of the August 2013 incident, we used MD5 to hash passwords. We began upgrading our password protection to bcrypt in the summer of 2013.” By admitting they had used the MD5 algorithm to hash the passwords stolen by hackers, instead of the more secure bcrypt algorithm, Yahoo unnecessarily made these stolen passwords vulnerable to a variety of commonly-known attacks – a detail not lost upon security researchers, who blamed Yahoo for negligence in doing so.

MD5 and bcrypt are examples of hashing algorithms, which are commonly used to “scramble” passwords so that even if such hashed-passwords are stolen (like in Yahoo’s case), it provides an extra measure of security since the thieves still cannot read the original password.

Moreover, companies typically add extra security by adding a “salt” (simply a randomly-generated string of bits) to the original password before it’s run through the hashing algorithm – so if 2 users have the same password “abcdefg”, their hashed-passwords will be different (e.g. running the hash algorithm on “40r4389” + “abcdefg” vs. “9m4bgfa” + “abcdefg” will get you different outputs). This ensures that, even if a thief knows “abcdefg” always has a corresponding hash of “qwertyu” for a specific hashing algorithm, they won’t know the hashed-output of “40r4389abcdefg”.

There are several reasons why MD5 is considered a particularly insecure hashing algorithm, for a variety of attacks that are known to exploit its weaknesses – and why bcrypt is considered secure in contrast, simply because it is not susceptible to those same attacks. At least for security purposes, MD5 is considered a weak hashing algorithm because of two main reasons:

-

It is typically unsalted, and

-

Computing the MD5-hash of any input is fast – particularly, on an NVIDIA GeForce 8800 Ultra GPU, one can compute 200 million MD5 hashes per second.

Therefore, if someone wanted to crack an MD5-hashed password and recover the original text, they could conceivably guess 200 million possible combinations per second, seeing if the MD5-hashed version of each guess matched the hashed-password they had. Moreover, because one can run different parts of the MD5 hash algorithm in parallel, as technology and computing power advances, computing MD5 hashes will only get quicker. Now, theoretically, this shouldn’t be too much of an issue with MD5; the MD5 algorithm gives a hash that is 128-bits long, meaning that there are 2^128 possible hashes to check – even at 200,000,000 hashes per second, trying to crack one password could take more seconds than since the universe has existed. However, there are commonly-known attacks that find a way around checking such a large search space – for example, a dictionary or rainbow table attack.

Because people often use the same passwords, one can easily find online several lists of commonly-used passwords and their corresponding MD5 hashes. In such “dictionary” attacks, a thief compares their stolen hashed-password to lists containing only a few hundred-thousand common hashes – meaning, instead of needing a universe’s-worth of time to crack one MD5 hash, they could potentially crack thousands of MD5-hashed passwords a minute. Again, this works not only because the MD5 algorithm runs quickly, but because MD5 does not incorporate salting, the corresponding MD5 hash of “password123” remains the same regardless if it was stolen from Yahoo in 2013 or from some OutdatedCompanyX in 1996.

Rainbow table attacks are similar, except that to save on storing such large “dictionaries” of passwords and their corresponding hashes, an attacker can represent several passwords/hashes at once by “chaining” them together, and only remembering the first and last passwords of the “hash-chain”. Using a carefully-chosen “reverse” map function, that takes in a given hash and outputs another dictionary word (not its original word), one can “traverse” a hash-chain by computing the hash of its first word, mapping that hash to another word using the “reverse” function, and repeating until reaching the last word in the chain. If at any point when traversing a hash-chain, the current outputted-hash matches the hashed-password an attacker is trying to crack, the attacker can figure out the original password just by looking at the previous word in the chain. Thus, in a rainbow table attack, an attacker can further reduce the space needed to store all passwords and corresponding hashes in their dictionary (as a trade-off, spending more time computing hash-chains on the fly), just by storing the first and last words of a chain.

These are just two common examples of attacks known since 2005 to practically work in cracking MD5 hashed-passwords. Should a company decide to use salting with its MD5 hash, while still with less-than-optimal MD5, the number of possible common MD5 hashes an attacker would need to store in memory, to execute either of these attacks, would simply be more memory than most common computers could hold.

Bcrypt, instead, is considered a secure hashing algorithm and is resilient against such attacks. Besides its base algorithm (which is based off the Blowfish cipher algorithm) incorporating salting with all inputs, its main strength – in contrast to MD5 – is how slow it can take to compute its hash. To compute the particular hash for a specific given input, bcrypt relies on the underlying Blowfish algorithm’s “key-setup” phase to encrypt a given password and return the keys necessary to decrypt it. This key-setup phase, in the original Blowfish algorithm, requires an overhead of pre-processing ~4KB text-worth of memory in RAM – not much memory by itself, considering most 4,8,16GB computers available, but a considerable amount relative for the encryption/decryption of a single password.

Yet bcrypt’s algorithm can be configured to run this key-setup phase multiple times, in a variable number of “re-keying” rounds; it is called the “Eksblowfish” algorithm, for “expensive key schedule Blowfish”. Thus, even while doing this key-setup phase multiple times is not theoretically more secure than just running it once, bcrypt’s algorithm can be made to run arbitrarily slow. Furthermore, the Blowfish Cipher algorithm’s computation cannot be parallelized like MD5; the algorithm itself (which is based on another Feistel Cipher algorithm) mathematically requires initialization of 18 32-bit subkeys in order to create the key necessary for encryption/decryption of a particular password, and each of these subkeys is initialized depending upon the previous subkey’s initialization – and the initialization of a single subkey occurs in a way that also cannot be parallelized. Once the key has been created, it can also be of variable length (anywhere from 32 to 448 bits), and it is fairly straightforward and much faster to actually use the key to decrypt a bcrypt-hash; however, once another password’s hash is encountered, the key-setup phase must run all over again. As a result, creating the key to encrypt/decrypt for every particular password (& salt) can take an arbitrarily long time, in a way that cannot be exploited by advances in computing power, that can vary (in time and length) from configuration to configuration, and must take place to decrypt each hash; in this manner, bcrypt as a hashing algorithm succeeds in defending against many attacks.

As a reference, in the data-breach of Ashley Madison’s bcrypt-hashed passwords in 2015, a security expert attempted a common dictionary attack on the leaked passwords – on a GPU-rig tailored to cracking hashed-passwords, he averaged ~156 bcrypt-hashes per second; after 5 days non-stop, his dictionary attack could only guess 4007 “weak” passwords out of the 6 million he’d stored in memory. Moreover, due to a design flaw in Ashley Madison’s system that also encrypted these same passwords using MD5, researchers managed to crack 11+ million passwords in 10 days. In comparison, of the over-a-billion MD5-hashed passwords stolen from Yahoo, it is almost certain that hundreds of millions of user’s passwords had already been unknowingly cracked within weeks of the breach. Had they been hashed with bcrypt, the damage could have been limited to only thousands of the weakest passwords.

However, even by the late-2014 breach, while “the vast majority [of stolen passwords were hashed] with bcrypt”, without Yahoo specifying what “vast majority” meant, several have come to speculate the number of MD5-hashed passwords stolen to be ~5-15% – which would still be on the order of tens of millions of user-accounts potentially compromised. Moreover, because Yahoo’s announcements again did not specify, it has been speculated that the MD5 hashes did not incorporate salting; noting the importance of this potential flaw, one security researcher said that “[..] most important [thing] is whether the hashes, be they MD5, […], are salted. There is absolutely no excuse to use unsalted hashes.”

HTTP Cookies

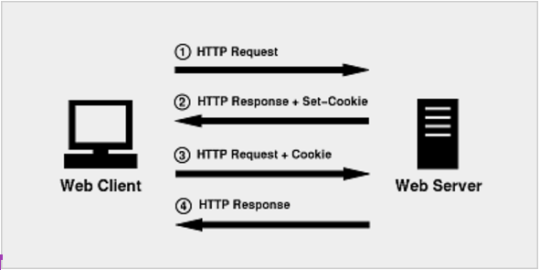

The main method in which the attackers stole users’ information was through forged cookies. However, in order to understand this, it’s important to first understand what cookies are and the purpose that they serve. HTTP Cookies are arbitrary data stored in a user’s web browser by a given website. The data can be anything, such as items in a shopping cart, but it’s usually some sort of session or user identifier. The data is then automatically transmitted back to the issuing website alongside the HTTP request, every time the user accesses it.

The purpose of cookies is to make HTTP stateful. By default a website does not remember who you are or which items are in your shopping cart, even after you log in. Cookies solve that problem by having your browser remember everything the website tells it to, and then send that data back every time you load a new page.

There are a number of different types of HTTP cookies, but authentication cookies are the most common. They are used by websites to know whether a user is logged in or not, which can then use that information (such as a user ID) to determine whether to display a login page or your profile.

The security of such cookies depends largely on the issuing application, the user’s web browser, and the encryption of the cookie data. As such by default cookies are very vulnerable, and steps must be taken to ensure their confidentiality. If an authentication cookie is read by an attacker, he can gain access to data only intended for the users whose cookie is stolen.

Cross Site Scripting

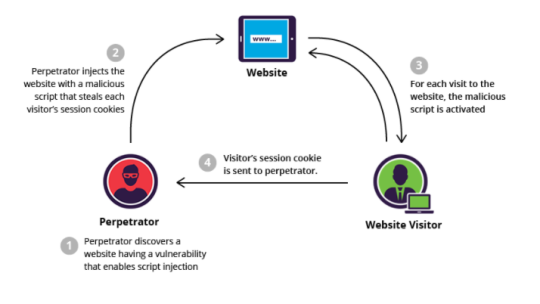

One of the many ways to exploit the vulnerability of cookies is through Cross Site Scripting (XSS). In its essence, it allows an attacker to inject a client-side script into websites which is then viewed by users. In short, it uses the website as a means to attack its own users.

The effect of a Cross Site Scripting attack depends on the scripts used, the data handled by the vulnerable website, and exactly how vulnerable the website is. It can range from something as trivial to modifying the page, to stealing cookies, tracking users actions, and much more.

HTML allows JavaScript through the use of the <script> tag. The contents of the tag will be executed by the browser upon loading the HTML file. This script can contain code that will steal a cookie, gain access to sensitive information on the website, or do just about anything with the available data.

The script can be injected into the website through for example a text box or instant messaging field that doesn’t sanitize its input, or by tricking the user to click on a malicious link that will inject the script directly into the website’s source upon loading. The script will then be executed in the browser of the user who sees that script, or in the case where the script is stored in for example a database, by every user that visits the website.

Yahoo! has had several Cross Site Scripting incidents in the past. In one particular case, Yahoo Mail allowed users to send non-sanitized text by email. Attackers exploited this by sending spam emails containing scripts that would steal the victim’s authentication cookies, use that to log into their email, and send even more spam.

Stealing/Forging Yahoo’s Cookies

Yahoo! disclosed alongside the breach in December 2016 that they believed an intruder had been able to create forged cookies that could allow him access to user’s accounts without a password. This was made possible through access to their proprietary source code. It is unknown whether this attack was linked to the data breach, but it is highly speculated that it may have been a contributing factor.

It is also believed that the previous September 2016 attack may have been made possible through cookie theft, but very little information has been disclosed by Yahoo! regarding the technicalities. This could either be due to a reluctance to share the information pending the acquisition by Verizon, or simply because they don’t know.

Incentives and Attribution

After the public disclosure of the data breach in late 2016, Yahoo did not disclose information on the 2013 breach, but pointed to a ‘state-sponsored actor’ for the 2014 data breach. Assumptions of the state-sponsor China, Russia, or North Korea which have all engaged in serious hacking targeting the U.S in the past. Some analysts suspected that blaming a ‘state sponsored actor’ was an easy excuse to deflect blame for their own security gaps.

Within the last few weeks, federal officials announced charges that allege a conspiracy between the criminal hackers behind the 2014 Yahoo Breach and the Russian Federal Security Agency (FSB). The names of the FSB agents that have been indicted are Igor Suschin and Dmitry Dokuchaev who are thought to have contracted two criminal hackers, Aleksey Belan and Karim Baratov. While the Russian spies were after secrets, the hackers were motivated by money.

According to the Justice Department, the spies gathered 500 million Yahoo accounts, which included information on diplomats, journalists, and Russian officials tied to the Kremlin. They also targeted intelligence and commercial value, such as the accounts of Russian investment banking firms and U.S airline executives. Meanwhile, the hackers parsed through the emails to look for gift card codes, credit card numbers and initiated a spam campaign. They manipulated the Yahoo search engine to find users searching information for erectile dysfunction and referred them to a Internet pharmacy that paid them commission. After the information was handed over, much of the data was then sold.

Since there is no extradition treaty with Moscow, putting the Russian suspects on trial will be difficult. However, the Justice Department believes that announcing these charges are useful for setting an example to the international community targeting the U.S. Although indicting the criminals does send a message, I believe that unless there are consequences the message will not be very effective for deterrence.

Prevention

There were multiple points of failure in Yahoo security that allowed multiple breaches to occur. Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer took much of the blame for refusing to invest in more robust security. Some included having a dedicated security team, maintaining a robust patch management system, and reviewing logs. However, the single critical point of failure is that the company stored all its data in one location which “becomes a treasure box for criminals”, says Vitali Kremez who is the cyber intelligence senior analyst at Flashpoint. Kremez points out that companies who adhere to superior cyber hygiene will separate user info across data center assets, which prevents attackers from gaining access to all critical information of the user, just by penetrating one database. By isolating their databases, Yahoo could have prevented the $350 million costs of the data breach that not only affected 500 million users, but also their negotiation with Verizon.

Acknowledgments

This work was done without any outside collaboration.

References

http://www.courant.com/la-fi-tn-yahoo-hack-20170315-story.html

http://fortune.com/2016/12/14/yahoo-discloses-breach-of-another-1-billion-accounts/

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2016/12/yahoo-one-billion-more-accounts-hacked/

http://fortune.com/2016/12/14/yahoo-discloses-breach-of-another-1-billion-accounts/

http://www.theverge.com/2017/3/15/14934654/yahoo-russia-hackers-charged-breach-security-fsb-criminal

https://yahoo.tumblr.com/post/154479236569/important-security-information-for-yahoo-users

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bcrypt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blowfish_(cipher)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feistel_cipher

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MD5

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collision_attack#Chosen-prefix_collision_attack

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainbow_table

http://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/400/why-cant-one-implement-bcrypt-in-cuda

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/12/15/yahoos_password_hash/