Hacking Team Attack

Abstract

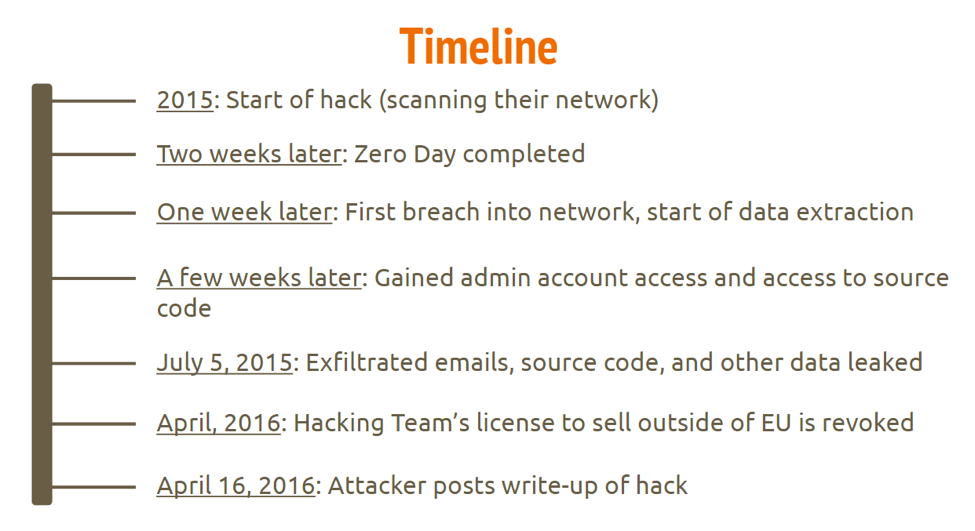

On July 5, 2015, over 400 gigabytes of Italian spyware company HackingTeam’s data was breached and leaked through BitTorrent and Mega. This data breach was announced through the company’s Twitter, which had been compromised by the attacker. The leaked data included HackingTeam’s passwords, emails, customer information, and source code. Phineas Fisher, who claims to be the sole perpetrator of this attack, released an extensive guide detailing how this hack was performed. In it, he discusses the vulnerabilities in HackingTeam’s network which allowed him to execute this attack, as well as his social and political motivations for following through with it.

In the Press

The press essentially took the side of the attacker, Phineas Fisher, painting a picture of HackingTeam as a villainous corporation. This was mainly due to the revealed sale of their spyware systems to countries with repressive regimes[1], which HackingTeam had previously attempted to cover up. The press focused on these sales, framing HackingTeam as a proponent of a shadowy global industry, which uses internet surveillance as a political weapon.

The press also bashed HackingTeam for their poor security practices, attacking them for their methods of securing their information. Specifically, HackingTeam’s shockingly bad password[24] choices were frequently discussed. Not as much media focus was placed on the issues within HackingTeam’s database structure, which heavily contributed to the success of Fisher’s attack. As far as the morality of Fisher’s actions, little emphasis was placed on whether he was right or wrong to attack this corporation in this way. Instead, the media targeted the immorality of HackingTeam’s actions through the countries to which they chose to sell their surveillance capabilities.

Underlying Technical Issues

Because of the nature of HackingTeam as a spyware authoring company, Phineas Fisher entered HackingTeam’s network not with phishing attempts but with careful network access. Phineas discovered a Joomla blog, email server, and a host of embedded devices on their public facing network. He chose to exploit an undisclosed embedded device by writing a patched backdoored firmware installed using a remote root exploit found by reverse engineering the device[14].

Once under control of the embedded device, Phineas scanned the network and listened to traffic to discover unauthenticated (by default) MongoDB instances containing audio of self-spying from test instances of their RCS (Remote Control System) Software and internal documentation. Nmap also discovered iSCSI devices (networked storage devices) in HackingTeam’s subnetwork. Phineas port-forwarded these devices and mounted them to a VPS which he controlled using tgcd and other command-line tools.

Once inside, he discovered multiple backups of virtual machines, including one of the company’s Exchange Server which he remotely mounted. Once inside its file system, he extracted passwords from the registry hives using creddump7, including credentials for a local administrator account which was still valid.

Because he had access as Domain Admin, he had control of the entire network and immediately began to download emails with PowerShell’s New-MailboxExportRequest through a SOCKS proxychain to remain undetected. He moved laterally through the network stealing passwords out of memory using mimikatz.

At this point the source code was still missing. Phineas spied on sysadmins and installed keyloggers and screen scrapers on their machines. He waited until Chris Pozzi, one of the sysadmins, mounted his Truecrypt volume then copied the files. He found plaintext passwords stored within this volume.

The source code could be found on the local git server with the passwords acquired via the Truecrypt drive. Twitter and Gitlabs accounts were compromised using the “forgot my password” function with access to HackingTeam’s mail server and everything was leaked soon after[26].

Suggestons for Prevention

The initial entry into the network through the 0day exploit in the embedded device was most likely not preventable by HackingTeam. There were, however, multiple points at which the progression of the attack could have been stopped, or at least slowed. HackingTeam could have required authentication to their MongoDB instances, which would have prevented their test instances of RCS and their recorded video and audio from being leaked.

Additionally, HackingTeam could have secured their iSCSI devices better. In the documentation leaked by the attacker, HackingTeam notes that the iSCSI devices should not be accessible from the portion of the network that the attacker was on, though they clearly were accessible. HackingTeam could have prevented access to the iSCSI devices by simply not making them accessible to all of their internal network. Furthermore, iSCSI supports authentication protocols (CHAP in particular), which should have been set in order to prevent unauthenticated access[25].

Even with access to the iSCSI devices and the backups that they contained, the attacker could have been thwarted by simply encrypting the backups of important data, such as the virtual machines. Without the encryption key, the attacker would have been unable to recover passwords from the virtual machines and thus may have been unable to compromise the mail server and domain admin account.

Quite possibly the most glaring weakness in HackingTeam’s security was their use of weak passwords[24]. It’s generally advised to use long and random looking passwords, though this wouldn’t have had much of an effect on this attack, since the passwords were all found in plaintext. The main improvement that HackingTeam should have made with their password use would be to not use the same password for multiple services. If the same passwords had not been used between the GitLab and user accounts, then the attacker would not have been able to steal the company’s source code so easily.

One last preventative measure that HackingTeam could have employed is simply not using services that store credentials in plaintext. The attacker was able to compromise a local admin account on the exchange server because the BlackBerry MDS service has a local admin account whose credentials are stored in plaintext. Similarly, other passwords, including the domain admin credentials, were dumped in plaintext from memory, which could have been prevented by using more updated versions of Windows that don’t store plaintext WDigest credentials in memory.

Incentives

In an exclusive Interview with Motherboard, Phineas Fisher shares that his inspiration for the attack came from a series of articles published by CitizenLab that suspected Hacking Group was responsible for selling RCS to countries with repressive regimes [14, 19, 20, 21]. When asked what his motivations for the attack was, Fisher confesses he didn’t expect to stop the company by leaking data and is quoted as saying it was primarily “for the lulz” [5].

But his views on HackingTeam and their activity is made clear in his Pastebin write-up, where he speaks about David Vincenzetti, CEO of HackingTeam: “I see Vincenzetti, his company, his cronies in the police, Carabinieri, and government, as part of a long tradition of Italian fascism” [14]. Like Gamma Group, the surveillance group Fisher had hacked previously, there was strong evidence that Hacking Group had been selling their software to governments considered to be repressive: “The difference between authoritarian regimes and ‘democratic’ ones is that HackingTeam customers jail, torture and kill, where the ‘democratic’ ones have gentler ways of managing dissent” [14]. Though his stated motive was indeed “lulz”, these quotes imply Fisher had greater moral drive to expose injustice.

On July 5th, 2016, Fisher exfiltrated all of HackingTeam’s private data including emails, internal documents, and source code for their software. As a result of this, the public lost trust in HackingTeam, both because of the embarrassment of a security group being attacked and that there was now proof they had lied to the public about which countries they had sold their software to[22]. Months later, Italy stripped HackingTeam of their license to sell their software outside of the European Union which compromised much of their international business[23].

Legal and Ethical Issues

HackingTeam and Phineas Fisher are considered to have violated the law, the former for trading with repressive governments, the latter for unauthorized breaching of HackingTeam’s servers and leaking their private information. Fisher himself even comments on his actions and their legality and ethics. When told that what he is doing is illegal and that HackingTeam’s actions could be considered legal, Fisher comments that “legal versus illegal is almost inversely proportional to right and wrong”, implying that even though his actions were illegal he believed what he was doing was right; similarly, that Hacking Group’s actions were wrong even though they were technically legal.

When considering ethics this hack becomes very nuanced and difficult to boil down to a consensus. Much of the media depicts Phineas Fisher as a vigilante, taking down the corrupt company giving spyware to other malicious organizations and airing their dirty laundry; even Fisher himself believes he did the right thing as mentioned previously. But the fact remains that Fisher did not have authorized access to HackingTeam’s data and that his attack was a clear violation to their system. We are forced to compare one bad act against another.

Many of the reports in the news justify Fisher’s actions because he was able to recover data on HackingTeam that revealed their crimes. But what if he was unable to uncover any data, or what if CitizenLab had been wrong about their accusations? Would Fisher’s actions still be justified, simply because he thought that HackingTeam was acting unethically? Unfortunately this is not an answer we can answer with any simplicity. It is left up to the individual to determine what, or who, is right here.

Acknowledgements

This work was done without any outside collaboration.

References Used

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/06/hacking-team-hacked-firm-sold-spying-tools-to-repressive-regimes-documents-claim

- http://news.softpedia.com/news/finfisher-s-account-of-how-he-broke-into-hackingteam-servers-503078.shtml

- https://www.definisec.com/160510—what-you-should-know-about-the-hacking-team-breach.html

- http://www.networkworld.com/article/3057200/security/hacker-who-hacked-hacking-team-published-diy-how-to-guide.html

- https://www.wired.com/2015/07/hacking-team-breach-shows-global-spying-firm-run-amok/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hacking_Team

- http://www.pcworld.com/article/3058014/hacker-this-is-how-i-broke-into-hacking-team.html

- https://arstechnica.com/security/2016/04/how-hacking-team-got-hacked-phineas-phisher/

- http://www.csoonline.com/article/3058764/security/hacking-team-postmortem-is-something-all-security-leaders-should-read.html

- https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2016/04/19/how-hacking-team-got-hacked/

- https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/the-vigilante-who-hacked-hacking-team-explains-how-he-did-it

- https://blogs.microsoft.com/microsoftsecure/2016/06/01/hacking-team-breach-a-cyber-jurassic-park/

- http://gizmodo.com/this-hackers-account-of-how-he-infiltrated-hacking-team-1771504896

- http://pastebin.com/raw/0SNSvyjJ

- https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/hacker-phineas-fisher-hacking-team-puppet

- https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/a-hacker-claims-to-have-leaked-40gb-of-docs-on-government-spy-tool-finfisher

- https://github.com/rmusser01/Infosec_Reference/blob/master/_site/Draft/Draft/Interesting%20Things%20Useful%20stuff/Writeup%20of%20Gamma%20Group%20Hack.txt

- http://www.hackingteam.it/news/2016/04/18/on-our-security-breach.html

- https://citizenlab.org/2014/02/hacking-team-targeting-ethiopian-journalists/

- https://citizenlab.org/2014/02/mapping-hacking-teams-untraceable-spyware/

- https://citizenlab.org/2014/02/hacking-teams-us-nexus/

- http://mashable.com/2014/02/23/hacking-team-spyware-governments/#kLhiphQ.RmqD

- https://www.ft.com/content/74d87c9e-053c-11e6-96e5-f85cb08b0730

- http://www.zdnet.com/article/no-wonder-hacking-team-got-hacked/

- https://library.netapp.com/ecmdocs/ECMP1196995/html/GUID-3FC8A37A-FFCC-4070-A9F0-1B9B3FB79BF8.html

- https://github.com/hackedteam