Bangladesh National Bank SWIFT Attack

Abstract

In early February 2016, the Bangladesh Central Bank was the victim of an elusive malware attack that attempted to steal more than $951 million from the bank’s reserve accounts. Using a purpose-built piece of self-concealing malware to exploit the bank’s implementation of SWIFT financial messaging, the attackers instructed the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to route funds from the Bangladesh Central Bank to dozens of accounts throughout southern Asia. While the heist was discovered before the entire $951 million cleared, a total of $81 million was stolen from the Bangladesh Central Bank and remains missing in the Philippines. A collective meeting between the corresponding banks and the SWIFT organization formally concluded that the attack took advantage of weaknesses in the local banks’ security, and that SWIFT’s core messaging systems were not compromised in any way. Despite this conclusion, several similar attacks occurred at banks in Ecuador and Vietnam shortly thereafter, calling into question the security of SWIFT software that implements the messaging services. In this report, we will examine the press coverage of the heist, legal matters surrounding this attack, the attack strategy and malware execution, potential prevention strategies, and the problematic nature of attribution.

What is SWIFT?

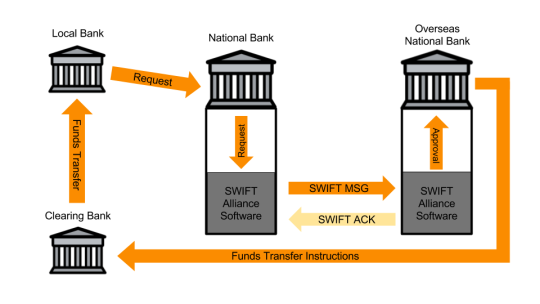

SWIFT is a secure financial messaging system that allows banks to communicate international banking transactions. SWIFT does not perform the actual funds transfer– rather, it is a secure messaging system that tells corresponding banks what amount to transfer and to where. SWIFT offers a variety of software that banks must purchase to access and communicate via the SWIFT network. Without getting too deep into an explanation of international banking procedures, the SWIFT implementation utilized at the Bangladesh Central Bank generally functioned as follows [13]:

- A local bank requests a transfer of money from an international bank.

- The national bank from the originating country generates a SWIFT message using SWIFT Alliance Access software instructing the overseas bank to transfer money to a specific account.

- The SWIFT message is sent to the corresponding international bank via the SWIFT network. The receiving bank generates a SWIFT ACK system message which is relayed to the originating bank; this ACK is not reviewed by an employee at the originating bank.

- The incoming SWIFT message is reviewed and authorized by a bank employee using the SWIFT Alliance Access software. Once approved, the message is loaded into an approved message queue.

-

At end of day, or batch close, the SWIFT Alliance software sends all queued approved messages to clearing banks to process funds transfer. The software also physically prints a record of all processed transactions for the day.

- The clearing bank processes the physical transfer of money that the originating bank requested. Note that in Figure 1, the final funds transfer described goes back to the local bank, but it is important to note that the funds transfer can be directed to any bank, international or otherwise. SWIFT is used when the funds requiring transfer are located in an international location.

The attack on the Bangladesh Bank exploited a vulnerability in the authentication mechanism utilized to access the SWIFT Alliance database used to store incoming and queued outgoing SWIFT messages. The attackers infiltrated the bank’s internal network and planted a specialized piece of malware on the Alliance workstations to fabricate SWIFT messages to route funds out of the Bangladesh Central Bank.

Figure 1: Standard SWIFT Implementation [13]

Bank System Access

How the attackers gained access to the Bangladesh Central Bank’s SWIFT workstations is largely believed have occurred via a breach of their internal network. Several reports cite a second hand, outdated switch as the vulnerable link that allowed the thieves to access the SWIFT workstations, especially when combined with the fact that the bank did not maintain any firewalls [2, 3, 5]. However, there is some speculation that an employee at the bank may have assisted the attackers by providing access to the machines [3, 5]. Regardless, the specific technical details of exactly how the bank was breached have largely remained withheld. One possible explanation for this is a potential lawsuit between the Bangladesh Central Bank and the New York Federal Reserve [12].

Alliance Database Access

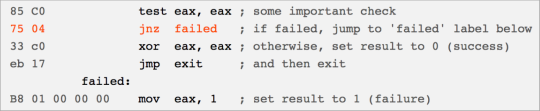

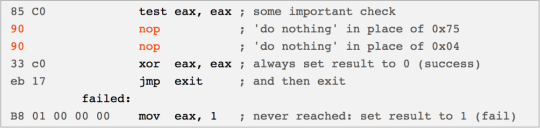

Once the attackers had sufficient access to the SWIFT workstation, a specially designed malware toolkit was installed. Under a correct implementation, access to the Alliance database, which contains all incoming and queued approved messages, is authenticated via a module file called liboradb.dll. The Alliance software uses this module file to process and authenticate employee login credentials, and subsequently regulate read and write access to the database. The malware created a patched copy of the dll file such that the authentication instructions could not fail. This was accomplished by patching two bytes of code such that two NOP statements were executed in the event of authentication failure, rather than denying access to the database. As such, unrestricted access to the database is granted to the calling program. The malware then used this patched dll to authenticate its own access to the Alliance database without using the Alliance software [5, 6, 10]. Figures 2 and 3 present lines of assembly pseudocode to illustrate the patching mechanism.

Figure 2: Correct liboradb.dll, courtesy of [6]

Figure 3: Patched liboradb.dll, courtesy of [6]

Attack Execution

Having gained access to the database, the malware used a predefined configuration file called gpca.dat to filter incoming messages for key phrases such as Convertible Currency, Available Currency, Client Credentials, and the authorization codes for the Bangladesh National Bank. Each of these pieces of information is stored in an incoming message, and stored in an unencrypted format in the Alliance database [6]. The malware then constructed SWIFT messages from the siphoned information, and used an SQL ADD statement to add the message to the approved message queue, bypassing any employee review or authentication. To remove evidence of the fabrication, the malware also removed the file from the print queue [6].

Attack Interception

Despite the fact that the attackers managed to execute nearly three dozen attacks, the New York Federal Reserve intercepted the attack when the attackers submitted a message requesting funds for the “Shalika Fandation” as opposed to the “Shalika Foundation.” At this point, the Federal Reserve alerted the Bangladesh Bank to the transactions. The banks were able to stop most of the transfers, but again $81 million was still stolen.

Attribution

The attack on the Bank of Bangladesh occurred in February of 2016 exploited the SWIFT messaging system costed the bank $81 million. Attribution has been hard to decide while clues point towards the group Lazarus the evidence is circumstantial at best. The code used in the attacks is mostly online and thus it is almost impossible to attribute blame [9].The attack caused an enormous public relations problem for SWIFT, and as a result SWIFT released over twenty press releases in the year that followed the initial attack. Their first effort was to create the customer security program which was released to help banks secure their own systems, detect threats, and share information between banks. Several months after the initial attack at SIBOS, a conference hosted by SWIFT, a new set of security measures were rolled out. SWIFT decided that starting in January of 2018 they would require a series of new measures for banks using their system [11]. It is unclear, however, the consequences for banks who do not meet these standards, and whether the noncompliant banks will be able to continue using SWIFT. Since the attack SWIFT has not made any mention of updating their own software as to prevent attacks of this nature. There still is, however, legal procedures occurring over the loss of $81 million dollars. This is a developing situation both legally and in the world as banks continue to be at risk from similar attacks.

Attack Prevention

First of all there is many ways for the bank to protect itself from those attack: upgrade the system, buy a new network switch, and install better anti-virus software. These could all prevent the Trojan attack from the Internet. More importantly, the bank could shift its system on the a secure cloud. Then the security of the system will be guaranteed by the third party rather that itself. However, Swift, the messaging system, could do an even better job on its Ack confirmation. It can have a separate program to check the Ack confirmation sent back rather than having a human to go through a the transactions. So that the attacker has to locate and compromise that program as well.

Motivation

The motivation is very simple – MONEY. This attack made the bank lose 81 million dollars. Moreover, it gives the attacker confidences, which causes the same attack on multiple banks in south asia: Vietnam, Ecuador, etc [8]. However, the brighter side is that now banks are all aware that this kind of attack exists and trying their best to build defense against the attack actively.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Sharon Goldberg for her feedback. This project was done without any outside collaboration.

References

[1] Anonymous. SWIFT attackers’ malware linked to more financial attacks. [Blog Post] Symantec’s Blog. May 26, 2016 https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/swift-attackers-malware-linked-more-financial-attacks

[2] Seraiul Quadir. Bangladesh Bank exposed to hackers by cheap switches, no firewall: police. [News] Reuters. April 22, 2016 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-bangladesh-idUSKCN0XI1UO

[3] Nicole Perlroth and Michael Corkery. North Korea Linked to Digital Attacks on Global Banks. [News] The New York Times. May 26, 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/27/business/dealbook/north-korea-linked-to-digital-thefts-from-global-banks.html?_r=0

[4] Anonymous. SWIFT comments on malware report. [Blog Post] Swift Report. April 25, 2016 https://www.swift.com/insights/press-releases/swift-comments-on-malware-reports

[5] Kim Zetter. That Insane, $81M Bangladesh Bank Heist? Here’s What We Know. [News] Wired. May 17, 2016 https://www.wired.com/2016/05/insane-81m-bangladesh-bank-heist-heres-know/

[6] Sergei Shevchenko. TWO BYTES TO $951M. [Blog Post] BAE Systems report. April 25, 2016 http://baesystemsai.blogspot.com/2016/04/two-bytes-to-951m.html

[7] Seraiul Quadir. How a hacker’s typo helped stop a billion dollar bank heist. [News] Reuters. Mar 10, 2016 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-bangladesh-typo-insight-idUSKCN0WC0TC

[8] Anonymous. SWIFT Banking System Was Hacked at Least Three times This Summer. [News] Fortune. Sep 26, 2016 http://fortune.com/2016/09/26/swift-hack/

[9] Sergei Shevchenko and Adrian Nish. LAZARUS’ FALSE FLAG MALWARE. [Blog Post] BAE Systems report. Feb 20, 2017 https://baesystemsai.blogspot.ro/2017/02/lazarus-false-flag-malware.html

[10] Sergei Shevchenko. The Evolution of Financial Malware - Bangladesh Bank Heist Case Study. [PPT] BAE Systems. 2016 http://cyberinbusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/CiB16_Sergei-Shevchenko_BAE-Systems.pdf

[11] Anonymous. SWIFT introduces mandatory customer security requirements and an associated assurance framework. [Blog Post] Swift Report. Sep 27, 2016 https://www.swift.com/insights/press-releases/swift-introduces-mandatory-customer-security-requirements-and-an-associated-assurance-framework

[12] Seraiul Quadir. Bangladesh Bank weighs lawsuit against NY Fed over hack. [News] Reuters. Mar 22, 2016 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-bangladesh-idUSKCN0WO2JQ

[13] Anonymous. Alliance Access: features and functionalities. [Blog Post] Swift Report. Mar 23, 2017 https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/interfaces-and-integration/alliance-access/features#topic-tabs-menu