WhatsApp Public Key Vulnerability

Abstract

In April 2016, Tobias Boelter discovered a flaw in WhatsApp’s implementation of the Signal protocol and demonstrated its vulnerability as a man-in-the-middle attack. Facebook, the owner of WhatsApp, defended their implementation as “design choice”. Subsequent media portrayals of the vulnerability range from a security flaw to a backdoor. We describe the security weakness that Boelter identifies, and a method to hack a GSM network. We also demonstrate how segments of the media gave a superficial portrayal of an important technical topic as communication security, and how research community came forward to mitigate the confusion among public.

Introduction

In January 2017, Manisha Ganguly at The Guardian announced the discovery of a vulnerability in WhatsApp’s security protocol, warning readers that “the company can read end-to-end messages”. She also claimed that privacy advocates allege that the vulnerability poses a “huge threat to freedom of speech.”[9] The news was divisive, invoking reactions ranging from depicting the vulnerability as a backdoor to dismissing the discovery as irresponsible reporting [2].

Tobias Boelter, a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley, discovered the vulnerability and published in a blog post in April, 2016 [10]. He showed that anyone who can hack a phone on a GSM network or convince WhatsApp to be someone, can read messages intended for that person. However, this vulnerability does not mean that the Signal protocol, which is the de facto standard for end-to-end encryption in instant-messaging, is broken. The vulnerability only exposes WhatsApp’s implementation of the Signal protocol.

Some segments of media bloated the vulnerability as a huge breakdown. Chris Mills states that a programming bug found in WhatsApp “theoretically allows Whatsapp to snoop on any encrypted messages sent over the platform” [15], overlooking that forward secrecy is ensured through WhatsApp’s implementation of Diffie Hellman key exchange. The Guardian’s report also sensationalises the issue because the alleged “backdoor” is only a particular choice of design.

WhatsApp officially denies the backdoor allegation, and many “cryptography experts” including Frederick Jacobs who worked on developing the messaging app Signal, refuted the claim, as well. Jacobs writes “It’s ridiculous that this is presented as a backdoor. If you don’t verify keys, authenticity of keys is not guaranteed. Well known fact.” [11].

WhatsApp’s Implementation of End-to-end Encryption

WhatsApp details its security protocols in a technical white paper initially published on April 5, 2016 and revised November 17 [8]. Users signing up for WhatsApp provide their cell phone number to receive a verification code via text. At registration time, every WhatsApp client generates three public-private key pairs, sent to the WhatsApp server: an identity key pair (I) , a signed pre-key pair (S), and a set of one-time pre-keys({O}).

WhatsApp employs Elliptic Curve Diffie Hellman (ECDH) key exchange to begin a cryptographic session between Alice and Bob. First, Alice retrieves Bob’s public keys from the WhatsApp server and generates an ephemeral public-private key pair E_Alice. Alice then computes the master_secret in the following way:

_master_secret = ECDH(I_Alice, S_Bob) ECDH(E_Alice, I_Bob) ECDH(E_Alice, S_Bob) ECDH(E_Alice, O_Bob)_

From master_secret, she generates the following keys via HKDF: a Root Key (32 bytes), used to generate Chain Keys; a Chain Key (32 bytes), used to generate Message Keys through HMAC-SHA256; and a Message Key (80 bytes), which is then splitted into three parts: an AES256-CBC key (encryption, 32 bytes), a HMAC-SHA256 key (authentication, 32 bytes), and an IV for AES256-CBC (16 bytes)[8].

Alice will send an encrypted message to Bob with E_Alice and I_Alice included in the header. Bob uses these public keys, along with his own private keys, to generate the same master_secret and from there the cryptographic keys, and will delete the one-time pre-key Alice uses to begin the session.

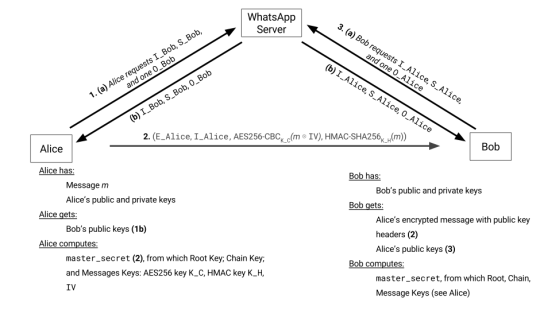

Figure 1: WhatsApp’s Encrypted Session Setup for Two Clients, Alice and Bob

Figure 1 depicts the key exchange. Alice asks for Bob’s public keys (1a) and receives them (1b). Alice sends a message to Bob with headers for Bob to set up a session. (2) Bob asks for Alice’s public keys (3a) and receives them (3b), and computes the master secret, establishing the cryptographic session.

If a user installs WhatsApp on a new device, they will generate a new set of keys. This will require a new cryptographic session for both users to set up. It is important to note that there is no vulnerability in the exchange protocol itself; the vulnerability occurs when Bob is required to generate new keys due to a new device or a reinstall.

The Vulnerability

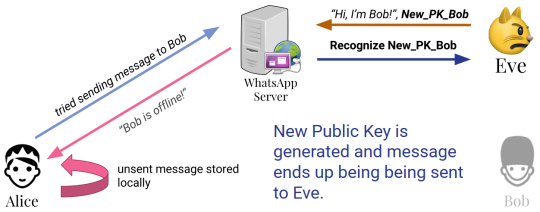

Figure 2: Illustration of the vulnerability

In this section, we explain the vulnerability found by Boelter. As we can see in Figure 2, Alice sends a message to Bob, when he is offline. The WhatsApp stores the unencrypted message locally, to be sent later. While Bob is offline, Eve hacks Bob’s phone or otherwise convinces WhatsApp to register her as Bob in their server, effectively forcing the start of a new cryptographic session, now between her and Alice. WhatsApp then encrypts the message from Alice’s phone with the new shared master_secret and sends it to Eve. As described above, Alice can be optionally notified about the new keys, but this notification comes only after the message is delivered. [1][2]

The attacker is anyone who can convince WhatsApp that s/he is one of the clients. One method of doing this is by hacking a GSM network to intercept the one-time verification code used by WhatsApp to verify that the new keys belong to Bob. Alternatively, a governmental agency can persuade WhatsApp to provide them access to a user’s identity and act as the user. In the scenario above describing the vulnerability in action, we can see how a government can act as Eve and get messages intended for a particular user. We now explain a method by which a hacker can impersonate a WhatsApp user by attacking a GSM network.

Today’s GSM network uses Signaling System No. 7 (SS7), a standard developed in 1970’s[7]. In a GSM network, a mobile device is connected to a base station, which then connects the mobile device to the GSM network so that mobile devices can communicate with each other. Our proposed method uses fake base station in a GSM network to obtain a user’s GSM network identifiers.

Bob is known in the GSM network by two identifiers: an International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) and a Unique identifier of a SIM card (USIM). If an attacker wants to impersonate Bob, she needs to know these identifiers which are privately kept in the GSM network.

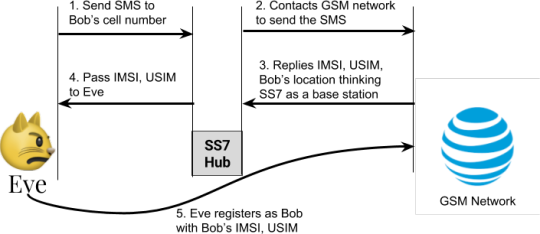

Figure 3: Eve employs an SS7 hub to impersonate Bob on a GSM network

To get access to these identifiers, an attacker may use an SS7 hub, available on the market for $300-500[4][5]. An attacker registers the SS7 hub to a GSM network to function as a fake base station. Important point to note is that this registration is not easily possible in most countries, but can be done in some of them. Figure 3 shows how an SS7 hub is used to get Bob’s IMSI and USIM number. Let us assume that the attacker’s name is Eve, who has bought a SS7 hub and registered it as a base station in GSM network. Eve, first, tries sending an SMS to Bob’s publicly available cell number (1). As she attempts sending the SMS using the SS7 hub, the SS7 hub contacts the GSM network to send the SMS (2). Upon receiving the request to send an SMS, the GSM network thinks that some base station is asking for information on where to send an SMS, intended for Bob. Therefore, the GSM network provides Bob’s IMSI and USIM, including its current location (the nearest base station of Bob) (3). The SS7 hub passes Bob’s IMSI, USIM to Eve (4). Eve then successfully register as Bob to the GSM network (5). It is important to note that if Eve is able to register her SS7 hub in any part of the globe, then she can carry out this attack. This is especially true if Bob’s registered GSM network is poor in recognizing malicious queries.

Incentives

Currently, there is no prominent example of this vulnerability being exploited. However, there are clear incentives for it to be, as sensitive information might be sent along WhatsApp. A government agency can intercept messages between a journalist and his/her source, to defend a corrupt government. There are many other possible scenarios, where foreign threats can try to attack by hacking GSM network. We believe that, since WhatsApp clearly is more concerned with the usability of their application rather than total security (undermining their “Security is in our DNA” marketing)[8], the concerned parties should not use WhatsApp to exchange sensitive information.

Legal Security Definitions

The WhatsApp public key vulnerability and corresponding press coverage underlies a larger discussion of the legal definitions of network security terminologies. The frequently used term is “backdoor,” which The Guardian used to describe the exploit [9]. This label was fiercely rejected by Open Whisper Systems (OWS), the group responsible for developing Signal Protocol, used by WhatsApp. OWS explicitly denied any such notion of a backdoor, saying “The fact that WhatsApp handles key changes is not a ‘backdoor’, it is how cryptography works”[16]. We as a group believe, in agreement with OWS and the vast majority of the cryptography and security research community, that this is, in fact, not a backdoor.

In addition, WhatsApp framed this as a design choice in order to allow the client to be “non-blocking” (i.e., messages will be re-sent without blocking to re-verify the key changes)[16]. We have shown that this “design choice” reduces the security of WhatsApp to the security of the GSM network, and that, since the GSM network can be exploited, so too can WhatsApp. Therefore, we argue that WhatsApp’s security partially depends on GSM network’s security, but also assert that the vulnerability is not a backdoor. Finally, when a user is executing a closed-source program, such as WhatsApp, he/she is already relying on the company’s integrity. Therefore, we can hope that WhatsApp properly maintains its security promises and does not compromise, in any external pressure.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Prof. Goldberg for her feedback. This work was done without any outside collaboration.

References

[1] Tobias Boelter. WhatsApp Retransmission Vulnerability. [Blog Post] Tobias Boelter’s Blog. April 16, 2016 https://tobi.rocks/2016/04/whats-app-retransmission-vulnerability/

[2] Zeynep Tufekci. _In Response to Guardian’s irresponsible reporting on WhatsApp: A plea for responsible and contextualized reporting on user security. _[Blog Post] Technosociology. [Date Unspecified] http://technosociology.org/?page_id=1687

[3] Bruce Schneier. WhatsApp Security Vulnerability. [Blog Post] Schneier on Security. 17, January, 2017. https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/01/whatsapp_securi.html

[4] Ilja Shatilin. How easy is it to hack a cellular network. November 24, 2015 https://blog.kaspersky.com/hacking-cellular-networks/10633/

[5] Samuel Gibbs. SS7 hack explained: what can you do about it? April 19, 2016 https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/19/ss7-hack-explained-mobile-phone-vulnerability-snooping-texts-calls

[6] Attacks based on GSM Networks. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobile_security#Attacks_based_on_the_GSM_networks

[7] _Signalling System No. 7. _https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signalling_System_No._7

[8]_ WhatsApp Encryption Overview. Technical white paper._ https://www.whatsapp.com/security/WhatsApp-Security-Whitepaper.pdf

[9] Manisha Ganguly. WhatsApp vulnerability allows snooping on encrypted messages. Guardian News. 13, January 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jan/13/whatsapp-backdoor-allows-snooping-on-encrypted-messages

[10] Tobias Boelter. _WhatsApp vulnerability explained: by the man who discovered it Tobias Boelter. Guardian News. _16, January 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jan/16/whatsapp-vulnerability-facebook

[11] Selena Larson. There’s no ‘backdoor’ in WhatsApp. CNN. 13, January, 2017. http://money.cnn.com/2017/01/13/technology/whatsapp-backdoor-false/

[12] David Glance. Was The Guardian’s WhatsApp reporting irresponsible or fake news?. The Wire. 1, January 2017. http://theconversation.com/was-the-guardians-whatsapp-reporting-irresponsible-or-fake-news-71749

[13] Abigail Beall. _WhatsApp messages may NOT be private: Major security flaw means governments and hackers could have access to your texts. _The Daily Mail. 13, January 2017. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-4117328/Facebook-read-private-WhatsApp-messages-Security-flaw-means-texts-intercepted-governments-hackers.html

[14] Kif Leswing. Top Security Expert: ‘There is no WhatsApp backdoor’. Business Insider. 13, January, 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/top-security-expert-there-is-no-whatsapp-backdoor-2017-1

[15] Chris Mills. WhatsApp bug allows viewing of encrypted messages. BGR. 13, January 2017. http://bgr.com/2017/01/13/whatsapp-encryption-broken-key-generated-nsa-oh-no/

[16] Open Whisper Systems Blog Post. 13, January 2017. https://whispersystems.org/blog/there-is-no-whatsapp-backdoor/