The Attacks on the Democratic National Committee

Abstract

During the summer of 2015 and then again in April 2016, the Democratic National Committee systems were infiltrated by two adversaries known as Cozy Bear (aka APT29, CozyDuke) and Fancy Bear (aka APT28, Sofacy), respectively. While it wasn’t until after Fancy Bear infiltrated the systems that any compromise was apparent, Cozy Bear managed to operate within DNC systems for almost a full year, largely in part to poor communication and investigation on the part of the FBI and DNC staff. After Cozy Bear had initially infiltrated DNC systems in July of 2015, an FBI operative had reportedly alerted DNC technical staff of a potential breach via a phone call a few months later. Without any protocol for confirming the identity of the FBI agent and being unable to confirm the presence of suspicious system activity, the DNC staffer assumed the call to be a hoax and the matter wasn’t addressed with confidence again until Fancy Bear’s infiltration almost a year later [8].

In May 2016, both groups were identified by CrowdStrike, a prominent cybersecurity company, and were promptly removed from the systems within hours of being detected. While in the DNC system, these groups were presumably harvesting information, both from documents and email conversations between DNC workers in order to allegedly interfere in the 2016 US Elections. In popular media and from officials in the U.S. government, it has been commonly alleged that these adversaries were both Russian-state government actors.

In this report, we will explore (1) the technical details behind the different strategies these groups used to perform their attacks on the DNC, (2) the evidence used to attribute these attacks to the Russian government, including critics of these attributions, (3) ethical and legal issues, and (4) methods of preventing such attacks.

Superficial/Sensationalist Issues

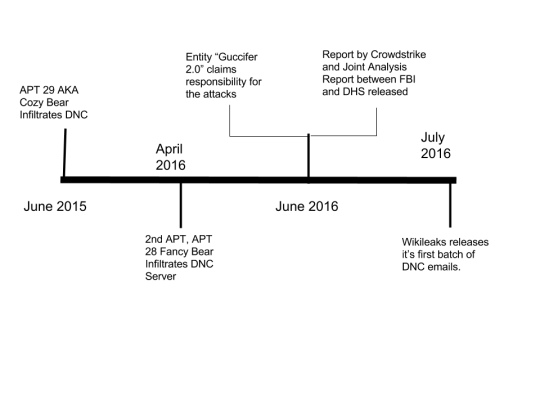

The news of the breaches first broke into the public sphere on June 15th, 2016, when Crowdstrike released their report detailing their analysis of the compromised DNC systems. The next day, midst the surge of stories put out by media outlets detailing the attacks as per the Crowdstrike report, an entity known by their Twitter handle Guccifer 2.0 claimed responsibility as the “lone hacker” behind the attacks[13], a claim this entity attempted to verify through the release of several official-looking documents. However, companies such as Crowdstrike have since refuted this claim, stating “Whether or not this posting is part of a Russian Intelligence disinformation campaign, we are exploring the documents’ authenticity and origin. Regardless, these claims do nothing to lessen our findings relating to the Russian government’s involvement, portions of which we have documented for the public and the greater security community. “[2] Regardless, Guccifer 2.0 remained an active part of news stories with each batch of leaked documents that would be released. Media outlets would soon have access to thousands of alleged private communications and documents from the breaches starting on June 22nd when WikiLeaks released the first batch of hacked emails.[9]

These and future batches of documents would become the focus of many articles, mainly in regards to alleged corruption within the DNC in regards to communications that fleshed out plans to undermine the candidacy of Senator Bernie Sanders as well as the various scandals surrounding key members of the DNC. Only days after the batch of emails released, Debbie Wasserman Schultz resigned from her position as DNC Chair, an action that only seemed to legitimize the leaked documents.

Events would remain relatively calm after the release of the Joint-Analysis Report by the DHS and the FBI until another batch of emails, known as the “Podesta Emails”, were released on October 7th. Discussion of these leaks as well as their potential connection to Russia would continue on throughout the remainder of the General Election and onward to the current day. With allegations of collusion between the Russian government and President Donald Trump’s advisory team, it does not appear that news of these breaches will exit the eye of the media for quite a long time.

[Figure 1 : Timeline]

The Underlying Technical Issues

Cozy Bear (APT29)

Cozy Bear’s attack began with a campaign of phishing emails on July 7, 2015 and utilized a two-stage malicious dropper to deliver its malware payload. The phishing emails utilized either would attach a file to the email directly or would provide a link to the downloadable file. The file in question was a self-extracting (.sfx) file. Upon execution of the .sfx file, a decoy media file alongside a secondary dropper is extracted to the %TEMP% directory, where the latter then begins its process of downloading the main payload [16].

The main payload comes in the form of a player.swf file. However, only about 16kb of its data consist of an actual flash component, while the actual file size is much bigger. The second-stage dropper begins decoding the file into an executable and drops it into %appdata%\Roaming where it then renames itself after legitimate, commonly executed software programs. After this, the secondary dropper cleans up after itself leaving the main payload to execute [16].

The payload, depending on small differences between iterations of the payload and depending on the organization analyzing it, may be referred to as miniDionis or SeaDuke/SeaDaddy. Primarily SeaDuke was the most commonly cited payload and is a Python-developed Windows executable (made into a binary via PyInstaller) which would first check its operating environment to ensure it is not being run on a virtual machine or any sand-box environment and would then set itself up accordingly. After setting up, it would maintain persistence primarily through its use of a single-line, obfuscated Windows PowerShell command which would take advantage of the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) system – a driver framework for Windows which allowed SeaDuke to continually reschedule itself [2].

Other means of persistence would include editing registry keys and the less-complex method of dropping .lnk files pointing to itself in the Windows Startup directory. From here, SeaDuke begins making outbound requests in order to interface with the command-and-control (C2) server, using cookies containing keys encrypted via the RC4 algorithm to encrypt and decrypt information it sends to and receives from the C2 server. During this, the C2 server sends SeaDuke a series of requests as JSON objects which it then parses and executes accordingly [17, 2].

Fancy Bear (APT28)

Fancy Bear operated through a two step attack. Fancy Bear’s attack started with a widespread email phishing campaign in order to steal credentials from DNC staff members. Once successfully retrieving the credentials, Fancy Bear would login into the (servers, systems) of the DNC where he would download two pieces of malware - X-Tunnel, and X- Agent.

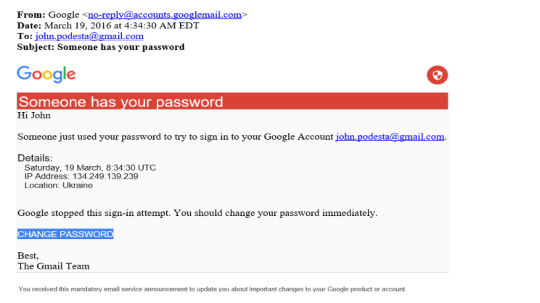

FancyBear’s spear phishing campaign sent spoofed emails, typically tricking victims to enter their credentials when asking them to reset their password. Figure a2 shows the email sent to John Podesta asking him to rest his password, by clicking the spoofed email address . The email was released as a part of the DNC wikileaks blowout which was released in (August/June). Threatconnect, another private cyber security forensic analytics company combed through the report by Crowdstrike. Among the IP addresses analyzed was one in particular 45.32.129[.]185 which was listed as a FANCY BEAR X-Tunnel implant. Threatconnect ran a reverse DNS search on the IP address, to find that one of the addresses it resolved to was the suspicious domain misdepatrmnet[.]com. [4] Subsequently running a lookup on the whois database, returned the email of frank_merdeux@europe.com on March 22, 2016. This evidence is significant for a couple of reasons. The domain misdepatrment[.] resembles closely that of the MIS Department whose address is misdepartment.com, a technology services provider, whose clients include the DNC–a slight misspelling, which turned out to be enough to trick the DNC staff.

[Figure 2 : The email sent to John Podesta, Chairman of the Clinton Campaign]

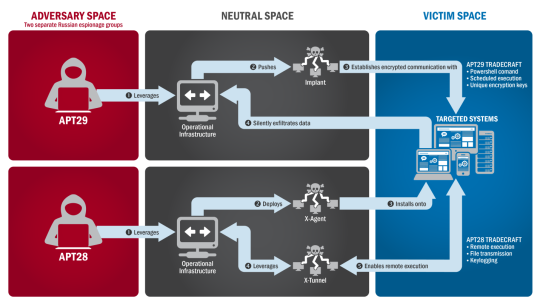

Once Fancy Bear gained password information of DNC officials, he proceeded to deploy X-Agent and X-Tunnel via RemCom, an open-source version of PsExec, allowing remote process execution on the targeted systems. The X-Agent Tool focused primarily on data retrieval, and performed keylogging, and file transmission to grab pertinent information. X- Agent also has been identified, as a tool used in a attack on Ukrainian artillery in late 2014 ,an attack also attributed to Fancy Bear . The second tool, X-Tunnel, focused on allowing Fancy Bear to cover his traffic .A report by invincea details the capabilities thoroughly, using the binary of the .exe file X-Tunnel was posing as to learn about it’s capabilities.[5] Using a deep learning algorithm, invincea extracts capabilities by matching strings to StackOverflow definitions. The clustering of X-Tunnel compared to other malwares, suggest that it was a tool built specifically for use against the DNC. X-Tunnel’s mains purpose was to establish a persistent encrypted connection to a pre-specified I.P address, even allowing the connection to pass through a NAT’ed firewall by wrapping traffic in protocols designed to pass the firewall. Using the connection provided by X-Tunnel, Fancy Bear could pull through the data retrieved by X-agent. Some vulnerabilities of the X-Tunnel, is that it’s traffic could have been discovered during “port knocking”, the process the tool goes through to find open ports on the Firewall. Figure (x) below depicts Fancy Bear’s attack through each step.

[Figure 3]

**Reviewing the Evidence **

On December 29, 2016, the Department of Homeland Security and Federal Bureau of Investigation released a Joint Analysis Report (JAR) – titled “GRIZZLY STEPPE – Russian Malicious Cyber Activity” – that provided evidence to supplement the claims made by several cybersecurity companies, including CrowdStrike and ThreatConnect, that the attacks committed by Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear were linked to the RIS, or the Russian Intelligence Services:

-

The general motivations Russia would have to interfere with the US election:

- “We are seeing a dramatic rise in cyber intrusion activity from the Russian government since the sanctions regime was put in place against them [by the Obama Administration in 2014]” said Dmitri Alperovitch, the co-founder of CrowdStrike.[15]

-

Tip the election in favor of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton.[8]2. The list of IOCs, or Indicators of Compromise, that was provided by the JAR. As its name would suggest, IOCs were any abnormalities that were identified within the DNC system and linked to malware used by Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear. [6]

-

Some malware were discovered to have been programmed to communicate with an IP address that had been previously associated with Fancy Bear in the past.[6]

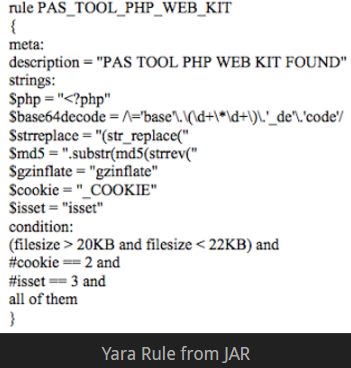

- The output received from a tool known as YARA (see figure 4), which is commonly used by malware researchers to quickly comb through a given system in order to find foreknown malware using signature based detection. YARA runs on a set of rules, each containing a list of strings and conditions – the former being used to search for values and the latter specifying criteria for detection – that are unique to a particular malware. The JAR included one such YARA rule: the PAS Tool WebKit – known to be a popular tool among Russian and Ukrainian hackers. The PAS Tool is essentially a web-shell, or a script, that an individual can upload to a web server to obtain remote access to the system. In the event of the DNC hack, this tool is believed to have been used to mask any traffic as normal web requests so the hackers could roam around the systems and exfiltrate information as they pleased.[3,14]

- The way in which the RIS, as reported by CrowdStrike, is known to operate is interesting to note. While Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear are believed to have neither collaborated nor have had any awareness of each other’s presence in the DNC systems, CrowdStrike points out that it is not an uncommon practice for Russia to deploy multiple espionage groups to attack the same system and try to obtain the same information. These groups have been conditioned to be incredibly competitive, so the sharing of intelligence is quite rare and groups might even attempt to steal from or compromise each other in order to gain the greatest favor from the Kremlin, which leaves Fancy Bear and/or Cozy Bear being state-funded a remaining possibility.[2]

- Reports mentioned two instances of cyberattacks in the past that used the same X-Agent malware that Fancy Bear used in their attack, one victim being the German Bundestag and the second being the French TV Network TV5Monde. Investigators from both these incidents suspected these attacks were committed by state-sponsored Russian hacking groups.[1,2]

[Figure 4]

How well does this evidence stand?

Soon after the JAR was released, a myriad of other individuals in the intelligence community have risen to critique the imputations towards Russia as premature and insubstantial. One such individual is the Errata Security CEO Rob Graham, who expressed concern for how much information the government has because as outsiders, we don’t know if they have “excellent information for attribution” or if “they’ve got only weak bits and pieces.” Critics have also noted the following logical fallacies that cast doubt on the legitimacy of the attributions:

-

The government neglected to provide technical detail on how the published IOCs worked

-

IP addresses alone are insufficient unless accompanied by web server logs to prove that commands to, for example, the PAS web shell came from them

-

The PAS Tool WebKit and X-Agent malware are both open-sourced (the former available on a Github repository and the latter was released by the antivirus provider Eset)

-

Lack of specifics on how the DHS and FBI determined Russian involvement because most claims have been made out of association

Prevention

The discussion of ethics or legality branches out farther than simply the unethical, and unsurprisingly illegal, act of releasing private information that without a doubt would disrupt the natural process of a Democratic election. Whilst those issues are certainly paramount and should be of concern to American citizens, the true reaching implications of this event lie in the issues of international law as well as the reporting of information obtained in unethical ways.

In our discussion of the criticisms by members of the intelligence community regarding the attribution reports, a great deal of confusion lies in the lack of evidence made public. Security blogger Bruce Schneider admits that “It’s one thing for the government to know who attacked it. It’s quite another for it to convince the public who attacked it… If the government is going to take public action against a cyberattack, it needs to make its evidence public. But releasing secret evidence might get people killed, and it would make any future confidentiality assurances we make to human sources completely non-credible. This problem isn’t going away; secrecy helps the intelligence community, but it wounds our democracy.”[11]. This lack of public evidence creates an even more puzzling situation when combined with the severe lack of solid international cybersecurity law. Even if the international community were able to come to a consensus on such laws, governments would face the issue Schneider describes in that they would be forced to release secret evidence in order to have any hope of making a judicial case.

In regards to the ethical implications brought to light by these breaches, there has been a large debate surrounding the backlash journalists received by reporting on documents put out by WikiLeaks. During an NPR segment, host Tony Cox goes into detail on the various arguments on both sides of the question of whether or not it was ethical to publish the leaked documents. These arguments boil down to an important question raised by intelligence columnist Robert Baer: “Who decides what is put out in the public?”[12]. Supporters of WikiLeaks state that the public has a right to the potentially damning information released, whilst opponents criticize the “reckless” nature of how WikiLeaks pushes information into the public sphere without redaction to protect the safety of certain individuals. Regardless of the stance one might take on this issue, it is something that will most certainly be discussed for years to come as the inevitability of further leaks put out by WikiLeaks seems certain.

Cybersecurity Recommendations for Enhanced System Security

We have compiled the following list of precautions that we recommend the DNC or any other organization take in order to prevent future breaches similar to those we have discussed:

-

Staff Training: Knowing not to enter credentials on any site that isn’t secure (Whether it was visited through a link in an email or isn’t deemed a secure connection by your browser). Knowing how to check the validity of a sender to spot spoofed email addresses.

-

Identification Protocols: Having a system to confirm the identity of U.S. government officials and law enforcement, specifically in reference to the lack of identity confirmation by the special agent for the FBI in September of 2015.

-

Application Whitelisting: Whitelisting will prevent any program except for those specified from running, therefore stopping malicious software from running.

-

Restrict Administrative Privileges: In order to reduce the possible damage of an actor gaining control of a staff member’s credentials, restrict privileges based on what the user actually would need for their duties.

-

Regular Security Audits: Perform regular audits of transaction logs in order to spot suspicious activity. Focus on regularly employing techniques that will minimize the time it takes to be aware of an adversary’s presence in one’s systems.

Acknowledgements

This work was done without any outside collaboration.

Sources

-

https://arstechnica.com/security/2016/12/did-russia-tamper-with-the-2016-election-bitter-debate-likely-to-rage-on/

-

https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/bears-midst-intrusion-democratic-national-committee/

-

http://blog.erratasec.com/2016/12/some-notes-on-iocs.html#.WJKCFPkrKUl

-

https://www.threatconnect.com/blog/guccifer-2-0-dnc-breach/

-

https://www.invincea.com/2016/07/tunnel-of-gov-dnc-hack-and-the-russian-xtunnel/

-

https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/current-activity/2016/12/29/GRIZZLY-STEPPE-Russian-Malicious-Cyber-Activity

-

https://www.threatconnect.com/blog/tapping-into-democratic-national-committee/

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/us/politics/russia-hack-election-dnc.html

-

https://glomardisclosure.com/2016/07/25/timeline-of-the-dnc-and-akp-hacks-wikileaks-releases/

-

http://www.welivesecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/eset-sednit-part-2.pdf

-

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/01/attributing_the_1.html

-

http://www.npr.org/2010/11/30/131699467/is-wikileaks-release-brave-or-unethical

-

https://twitter.com/GUCCIFER_2

-

https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2013/10/using-yara-to-attribute-malware/

-

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/04/08/obama-to-putin-stop-hacking-me.html

-

http://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/07/tracking-minidionis-cozycars-new-ride-is-related-to-seaduke/

-

http://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/07/unit-42-technical-analysis-seaduke/