Apple vs. FBI

Abstract

The “Apple vs FBI” case hit the news in late 2015/early 2016, whose repercussions are still felt today. What started as an FBI terrorist attack investigation became a legal and ethical struggle that reached across the nation. The FBI was unable to gain access to a suspect’s phone since they did not know the phone’s passcode, so they went to Apple for help, asking them to create a backdoor to their products. Apple refused, stating it would compromise the security of all iPhones. This led to many arguments about who was right, some saying that Apple was wrong for making the security so strong that it puts consumers above the law, and others praising Apple for making the phones so protected and standing up for the security of their customers.

Superficial/Sensational Issues

In December 2015, married couple and ISIS followers Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik carried out a terrorist attack in San Bernadino, California, where 14 people were killed and 22 were injured at a company holiday party and training event. After the shooting, the couple fled and were later killed in a police shootout [1]. During the investigation of this attack, the FBI needed access to Farook’s iPhone 5c to gather evidence (last GPS locations, texts, phone calls, etc.) to find the motivation behind the attack and possible accomplices. However, the FBI quickly found that they were unable to get into this phone as Farook was the only one who knew the passcode, and the passcode is not stored on the device. In addition, his phone was set to automatically erase all data after 10 incorrect passcode attempts, thus stopping any attempts of the FBI brute forcing in.

How Could the Attack have been Prevented?

The FBI could have gotten some information from Farook’s phone through Apple’s cloud-based storage service, iCloud. Because this does not have the same security components as the phone itself, Apple will and has turned over crucial data stored in iCloud in investigations like this one. Apple suggested that the FBI try to connect his phone to a known Wi-Fi network, such as his home network, in the hopes that it would trigger an automatic backup so that the information could be recovered, since it had not been connected for 2 months [12]. However, the FBI tried to reset and change Farook’s iCloud password before consulting Apple, which ended up having the opposite effect of locking them out for good [20].

What options did the FBI have to get into this phone since they no longer had access to iCloud? First and second: either the FBI or Apple could get into the phone if they had access to the passcode. However, this clearly was not an option because the passcode was only known by Farook. Third: the user could get in, but Farook was killed in a shootout so this also was not an option. The only other option was for the FBI to go to Apple, demanding that they make software to allow the FBI to brute force Farook’s passcode. However, Apple did not want to make this software, leading the FBI to find a third party to get in. The details of how exactly this was carried out were not released. Court statements show that “the government has now successfully accessed the data stored on Farook’s iPhone and therefore no longer requires the assistance from Apple Inc.” [21] and give no further information on the subject.

FBI’s Incentives

The FBI initially had a search warrant for the phone, but since they could not get into the phone in question, they went to Apple for assistance. The FBI asked Apple to create a custom version of iOS that could be run from the phone’s RAM which would disable certain security features. Apple declined this request, so the FBI came back with a court order. This highlighted three key points: the software should disable the auto-erase security feature on iOS, enable the FBI to enter passcodes via a physical port or other protocol such as Bluetooth or Wi-Fi to help them automate the passcode entering process, and deactivate the auto-disable feature on the phone so that there were no delays between passcode entering attempts [23].

Apple’s Response

In a letter to their customers, Apple CEO Tim Cook addressed this issue as well as the dangerous precedent it set. He argued that creating this custom version of iOS had two “important and dangerous implications” [22]. The first point was that creating this software would make it easier to unlock an iPhone by brute force. It would intentionally weaken the product’s security and could put the privacy and safety of all customers at risk if Apple ever lost control of this software. Apple also stressed that this court order, if followed through upon, set a legal precedent and expanded the power of the government which would lead the company down a risky path. Apple did mention that creating this custom version of iOS was possible; however, they argued that once this software existed in the digital world, it could potentially be used on any iPhone [22].

Had Apple created this custom version of iOS, everything else would have been easy. Installing the software is something that an average iPhone user can do from the comfort of their own home. This requires putting an iPhone into Device Firmware Update (DFU) Mode, which is used as a last resort in recovering an iPhone. DFU Mode boots the iPhone into a low-level state, allowing the user to replace the operating system’s files, while keeping the user’s data intact and encrypted [13]. Once in DFU Mode, iTunes would send the iOS firmware image to the phone, running it from the device’s RAM. No passcode is required to restore the OS, which brings up the question: Why did Apple make it so easy to restore the OS via DFU Mode? There are many theories, but one possibility was that the decision was made in a usability vs. security tradeoff to provide a customer with an easy way to regain access to their phone if they ever got locked out.

The phone in question was an iPhone running iOS 8 which introduced new security features that made it more difficult to break into a phone. Had the phone been running iOS 7 or earlier, this custom version of iOS would not have been necessary.

Underlying Technical Issues

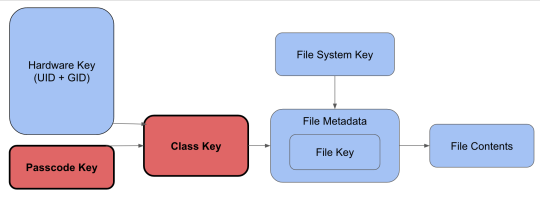

Figure 1: iOS Security Architecture

Starting with iOS 3 and the iPhone 3GS, Apple began to encrypt the full system with hardware-based AES full disk encryption. Contents are encrypted using numerous different keys, as seen in Figure 1. The two main keys that were relevant in this case were the passcode key and the class key. The passcode key is the alphanumeric passcode that only the user knows, and the class key specifies how the data is encrypted and when a passcode is necessary to unlock it.

There are two important types of class keys related to this case: Complete and Complete Until First Authentication (CUFA). A file encrypted with the “Complete” key means that the file is locked when the device is locked. Once the phone is unlocked, the file is accessible. Once the phone is locked, the decrypted class key is erased from memory and the file is locked until the passcode is entered once again. A file encrypted with the CUFA key means that the file is locked until the user unlocks the device after the most recent reboot. Once the phone has been rebooted, the file is locked and encrypted. Once the passcode has been entered after the reboot, the file is accessible until the phone is once again rebooted. The decrypted keys are lost from memory when the phone is rebooted, thus requiring the passcode to decrypt them again [18].

What is new in iOS 8 as compared to older operating systems? First, there is a 5 second delay for passcode attempts. Next, in operating systems pre-iOS 8, Apple could load a custom OS that would allow the device to decrypt all files without needing a passcode. Now, most of Apple’s app data (specifically the data needed for investigation purposes) is encrypted with the Complete or CUFA class keys. Anyone wanting to decrypt any iPhone data would need the iPhone’s passcode [18]. With this in mind, Apple cannot access the data without the passcode and will not create a backdoor to change the security features.

It is important to note that the iPhone in question was an iPhone 5c as opposed to an iPhone 5s or later. These newer phones have a security feature called the “Secure Enclave”, which makes it impossible to load the custom version of iOS that would disable the security features (delay between passcode attempts and erasing the phone after 10 failed attempts). The Secure Enclave contains its own UID and AES encryption engine which handles passcode verification, and is separated from the rest of the software. The main CPU requests the file’s keys from the Secure Enclave, which cannot be given without the user’s passcode. The Enclave is a separate CPU that is not under the kernel’s control. On older phones, compromising the kernel compromises the entire phone, including the passcode verification process. With the Secure Enclave, the security functions surrounding the passcode will always remain intact [10]. Apple does not release how they update the Secure Enclave because doing so would put it at risk of being compromised. This allows only Apple to be able to make any updates like disabling the security features, which they likely would not make.

Legal/Ethical Issues

Two main legal issues were presented in the Apple vs FBI case. Apple argued that the FBI did not have the right to use a court order to force them to write software because this would violate Apple’s First Amendment rights, as many consider code to be a form of freedom of speech [7, 8]. On the other hand, the FBI argued that through the All Writs Act, courts that have jurisdiction can compel the aid and cooperation of a third party in cases [9]. The All Writs Act has been criticized for being outdated, since it was made in the 18th century. Also, the Act should only be used as a last resort, the third party must be closely related to the case, and the burden must be temporary [8]. Arguably the FBI and the courts did use this court order as a last resort and since Farook’s phone was an iPhone 5c, the FBI considered the company to be closely related. Apple said that they are “no more connected to this phone than General Motors is to a company car used by a fraudster on his daily commute.” [8] Lastly, the final requirement of the Act was the least supported because complying to the court order would have been an extreme burden on both the company and the tech community. Therefore the All Writs Act should not have held in court, had the case continued. Apple was on the defensive during the case because the company understood that the issue was bigger than this case with this one iPhone.

Reinforcing Apple’s argument that once exploitative tools have been created they can be used by anyone, a few weeks ago, a hacker leaked 900gb of data that included user accounts along with iPhone, Android, and Blackberry device exploit techniques from the company Cellebrite. The leaker also included a Python script that executes all of these hacks along with a ReadMe file that said “@FBI Be careful in what you wish for.“ and “backdoorz” in ascii art [15]. This has put old iPhones in a very vulnerable state and reiterates how dangerous creating an exploit that can break into an iPhone is.

Conclusion

This case added to the ongoing debate on whether we are willing to compromise the security of our information and privacy in order to combat terrorism and other threats. Apple stated, “While we believe the FBI’s intentions are good, it would be wrong for the government to force us to build a backdoor into our products. And ultimately, we fear that this demand would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect.” [22] We believe Apple made the correct decision to fight the warrant and court order because complying with it would “be like providing a universal key that will permit law enforcement to break into anyone’s iPhone”. [5] The negative consequences of creating the backdoor would have outweighed the benefits. Security should be uncrackable, even if the algorithm is publicly available.

Acknowledgements

This work was done without any outside collaboration.

References

- “2015 San Bernardino attack.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Feb. 2017. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015_San_Bernardino_attack.

- Campbell, Mikey. “U.S. Attorney General voices concern over Apple’s iOS 8 security features.” AppleInsider. AppleInsider, 30 Sept. 2014. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://appleinsider.com/articles/14/09/30/us-attorney-general-voices-concern-over-apples-ios-8-security-features.

- Szoldra, Paul. “The big fight between Apple and the FBI is all Apple’s fault.” Business Insider. Business Insider, 17 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/apple-fbi-encryption-2016-2.

- “FBI boss ‘concerned’ by smartphone encryption plans.” BBC News. BBC, 26 Sept. 2014. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-29378172.

- Andrusewicz, Marie. “Apple Opposes Judge’s Order To Help FBI Unlock San Bernardino Shooter’s Phone.” NPR. NPR, 17 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/02/17/467035863/judge-orders-apple-to-help-investigators-unlock-california-shooters-phone.

- Selyukh, Alina, and Camila Domonoske. “Apple, The FBI And iPhone Encryption: A Look At What’s At Stake.” NPR. NPR, 17 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/02/17/467096705/apple-the-fbi-and-iphone-encryption-a-look-at-whats-at-stake.

- “First Amendment.” LII / Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law, 05 Feb. 2010. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment.

- Gross, Grant. “Apple vs. the FBI: The legal arguments explained.” Computerworld. IDG News Service, 26 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.computerworld.com/article/3038269/security/apple-vs-the-fbi-the-legal-arguments-explained.html.

- “28 U.S. Code § 1651 - Writs.” LII / Legal Information Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/28/1651#a.

- Ash, Mike. “Friday Q&A 2016-02-19: What Is the Secure Enclave?” Mikeash.com: Friday Q&A 2016-02-19: What Is the Secure Enclave? N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.mikeash.com/pyblog/friday-qa-2016-02-19-what-is-the-secure-enclave.html.

- Tikvah, Petah. “Cellebrite Statement on Information Security Breach.” Cellebrite. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.cellebrite.com/Mobile-Forensics/News-Events/Press-Releases/cellebrite-statement-on-information-security-breach.

- Lichtblau, Cecilia Kang and Eric. “F.B.I. Error Locked San Bernardino Attacker’s iPhone.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 01 Mar. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/02/technology/apple-and-fbi-face-off-before-house-judiciary-committee.html.

- Bright, Peter. “There are ways the FBI can crack the iPhone PIN without Apple doing it for them.” Ars Technica. N.p., 09 Mar. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://arstechnica.com/apple/2016/03/there-are-ways-the-fbi-can-crack-the-iphone-pin-without-apple-doing-it-for-them/.

- Roger Cheng March 4, 2016 12:35 PM PST @RogerWCheng. “11 juiciest arguments made in the Apple vs. FBI iPhone fight.” CNET. N.p., 04 Mar. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.cnet.com/news/iphone-apple-fbi-fight-11-juiciest-arguments-made-in-public-court-filings/.

- Broussard, Mitchel. “Hacker Leaks Cellebrite’s iOS Bypassing Tools, Tells FBI ‘Be Careful What You Wish For’” Mac Rumors. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.macrumors.com/2017/02/03/hacker-leaks-ios-bypassing-tools/.

- Cox, Joseph. “Hacker Dumps iOS Cracking Tools Allegedly Stolen from Cellebrite.” Motherboard. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/hacker-dumps-ios-cracking-tools-allegedly-stolen-from-cellebrite.

- Sieminski, Paul. “Automattic and WordPress.com Stand with Apple to Support Digital Security.” Transparency Report. N.p., 03 Mar. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://transparency.automattic.com/2016/03/03/automattic-and-wordpress-com-stand-with-apple-to-support-digital-security/.

- Schuetz, David. “A (not so) quick primer on iOS encryption.” DarthNull.org. N.p., 6 Oct. 2014. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.darthnull.org/2014/10/06/ios-encryption.

- “IOS Security Guide.” Apple. Apple, May 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. https://www.apple.com/business/docs/iOS_Security_Guide.pdf.

- Brandom, Russell. “Apple execs say county officials reset San Bernardino suspect’s iCloud password.” The Verge. The Verge, 19 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.theverge.com/2016/2/19/11075292/iphone-san-bernardino-icloud-password-reset/in/10800347.

- “Government’s status report.” The Washington Post. WP Company, n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://apps.washingtonpost.com/g/documents/national/governments-status-report/1913/.

- “Customer Letter.” Apple. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. http://www.apple.com/customer-letter/.

- “Order Compeling Apple, Inc. To Assist Agents in Search”. Web. 16 Feb. 2016. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2714001/SB-Shooter-Order-Compelling-Apple-Asst-iPhone.pdf.